Inquiry-Based Music Theory OER Text Book

1b Lesson - Labeling Pitches

Class Discussion

Our discussion will be written and edited here.

Further Reading

From Open Music Theory

The Keyboard

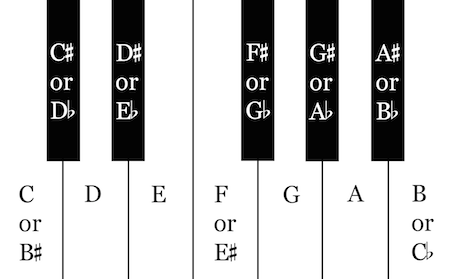

The keyboard is great for helping you develop a visual, aural, and tactile understanding of music theory. On the illustration below, the pitch-class letter names are written on the keyboard.

Enharmonic equivalence

Notice that some of the keys have two names. When two pitch classes share a key on the keyboard, they are said to have enharmonic equivalence. Theoretically, each key could have several names (the note C could also be considered D♭♭, for instance), but it’s usually not necessary to know more than two enharmonic spellings.

Octave Designation

When specifying a particular pitch precisely, we also need to know the register. In fact, if all you have is C-sharp or B-flat, you do not have a pitch, you have a pitch-class. A pitch-class plus a register together designate a specific pitch.

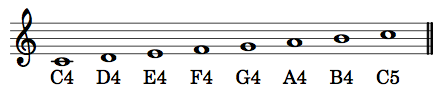

We will follow the International Standards Organization (ISO) system for register designations. In that system, middle C (the first ledger line above the bass staff or the first ledger line below the treble staff) is C4. An octave higher than middle C is C5, and an octave lower than middle C is C3.

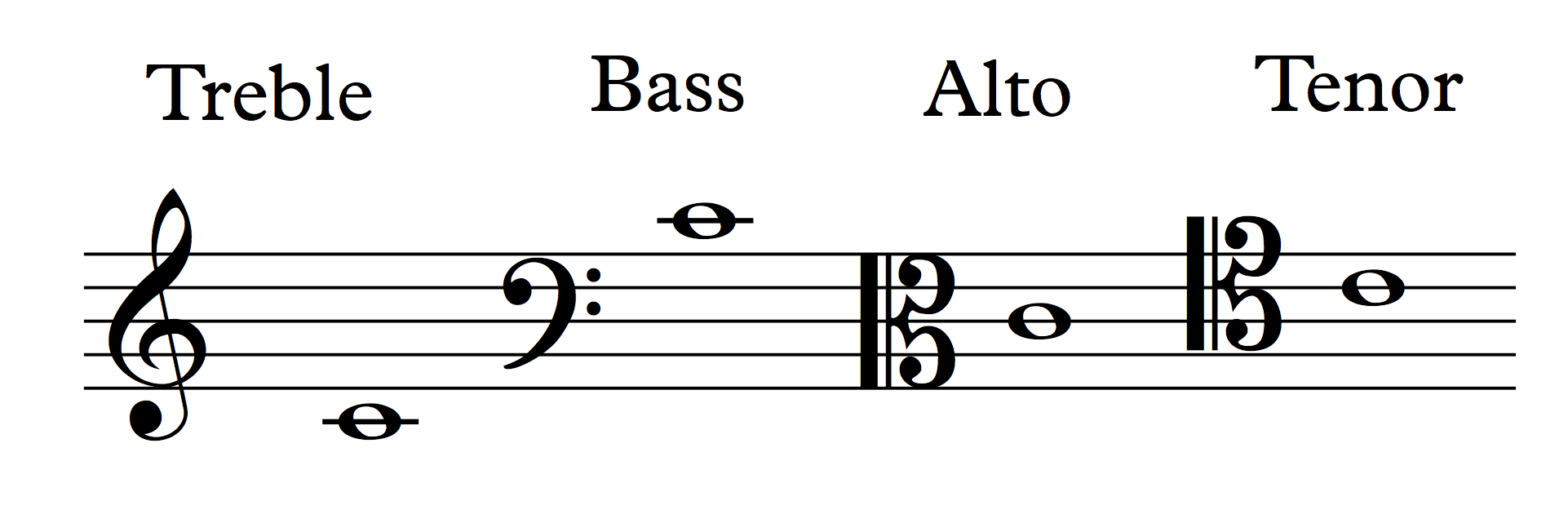

Here is the pitch C4 placed on the treble, bass, alto, and tenor clefs.

The tricky bit about this system is that the octave starts on C and ends on B. So an ascending scale from middle C contains the following pitch designations:

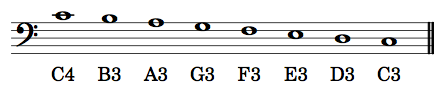

And a descending scale from middle C contains the following pitch designations:

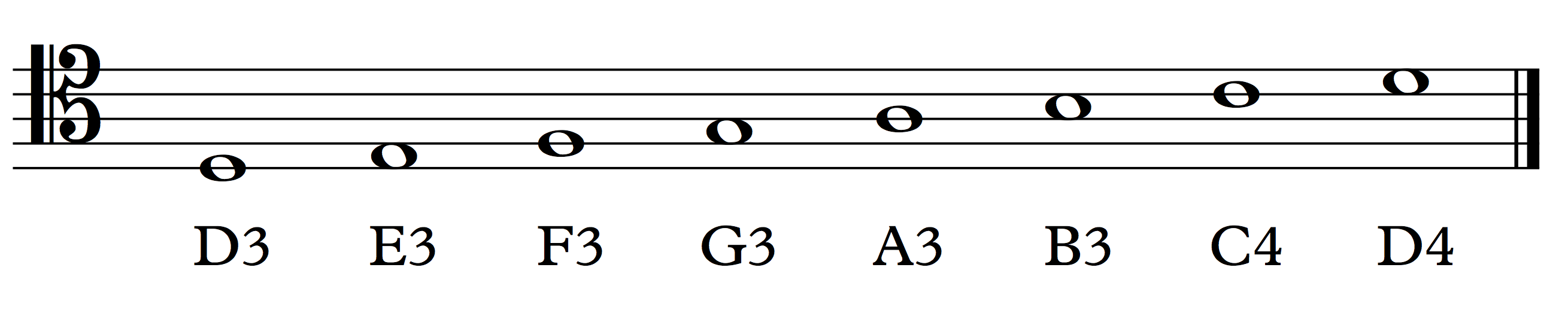

Pitches on the alto staff are as follows:

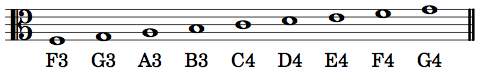

Pitches on the tenor staff are as follows:

Any accidentals follow the octave designation of the natural pitch with the same generic name. Thus a half step below C4 is C-flat4 (even though it sounds the same as B3), and a half step above C4 is C-sharp4.

Note that a complete designation contains both the pitch-class name (a letter name plus an optional sharp or flat) and the register (the ISO number indicating the octave in which the pitch is found). Unless both are present, you do not have the full designation of a specific pitch.