Inquiry-Based Music Theory OER Text Book

Embellishing tones

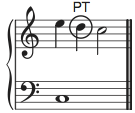

Passing Tone (PT)

A passing tone is a melodic embellishment (typically a non-chord tone) that occurs between two stable tones (typically chord tones), creating stepwise motion. The typical figure is chord tone – passing tone – chord tone, filling in a third (see example), but two adjacent passing tones can also be used to fill in the space between two chord tones a fourth apart. A passing tone can be either accented (occurring on a strong beat or strong part of the beat) or unaccented (weak beat or weak part of the beat).

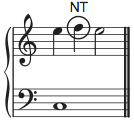

Complete Neighbor Tone (NT)

Like the passing tone, a complete neighbor tone is a melodic embellishment that occurs between two stable tones (typically chord tones); however, a complete neighbor tone will occur between two instances of the same stable tone. Also like the passing tone, movement from the stable tone to the neighbor tone and back will always be by step. A complete neighbor can be either accented or unaccented, but unaccented is more common.

Double Neighbor Figure (DN)

Like the complete neighbor figure, the double neighbor figure begins and ends on the same stable tone (typically a chord tone). Between those two instances of the stable tone are two embellishing tones — one a step above and the other a step below the stable tone being embellished. Though individually we may consider each of the two embellishing tones to be incomplete neighbors (below), working together in the double-neighbor figure they balance each other out and create a contiguous whole, with the overall stability of a complete neighbor. A double neighbor figure is typically unaccented.

Incomplete Neighbor Tone (INT)

The incomplete neighbor tone is an unaccented embellishing tone that is approached by leap and proceeds by step to an accented stable tone (typically a chord tone). Broadly speaking an incomplete neighbor tone is any embellishing tone a step away from a stable tone that proceeds or follows it (and is connected on the other side by leap), but other kinds of incomplete neighbor tones have special names and roles that follow below.

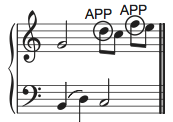

Appoggiatura (APP)

An appoggiatura is a kind of incomplete neighbor tone that is accented, approached by leap (usually up), and followed by step (usually down, but always in the opposite direction of the preceding leap) to a more stable tone (typically a chord tone).

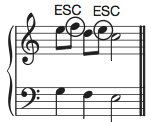

Escape Tone (ESC)

An escape tone, or echappée, is a kind of incomplete neighbor tone that is unaccented, preceded by step (usually up) from a chord tone, and followed by leap (usually down, but always in the opposite direction of the preceding step).

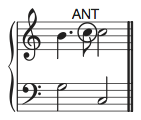

Anticipation (ANT)

An anticipation is essentially an otherwise stable tone that comes too early. An anticipation is typically a non-chord tone that will occur immediately before a change of harmony, and it will be followed on that change of harmony by the same note, now a chord tone of the new harmony. It is typically found at the ends of phrases and larger formal units.

Syncopation (SYN)

Syncopation occurs when a rhythmic pattern that typically occurs on strong beats or strong parts of the beat occurs instead on weak beats or weak parts of the beat. Like the anticipation, the syncopated note is an early arrival — it tends to belong to the chord on the following beat. Unlike the anticipation, the syncopation is tied into a note in that chord; it is not rearticulated. Rather than anticipating a note in the chord that follows, a syncopation is simply an early arrival.

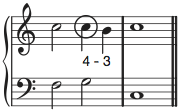

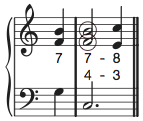

Suspension (SUS)

A suspension is formed of three critical parts: the preparation (accented or unaccented), the suspension itself (accented), and the resolution (unaccented). The preparation is a chord tone (consonance). The suspension is the same note as the preparation and occurs simultaneous with a change of harmony. The suspension then proceeds down by step to the resolution, which occurs over the same harmony as the suspension. The suspension is in many respects the opposite of the syncopation: if the anticipation is an early arrival of a tone belonging to the following chord, a suspension is a lingering of a chord tone belonging to the previous chord that forces the late arrival of the new chord’s chord tone. However, in composition and improvisation, the suspension must be treated with a great deal more care than the syncopation. The most common suspensions (and their resolutions) in upper voices form the following intervallic patterns against the bass: 9–8, 7–6, 4–3. (With the exception of 9–8, the pitch class of the resolution tone should never sound in another voice simultaneous with the suspended tone.) Instead of SUS, it is more typical to notate the intervallic pattern in the thoroughbass figures.

Retardation (RET)

A retardation is essentially an upward-resolving suspension. It is almost always reserved for the final chord of a large formal division (or a movement), and it frequently appears simultaneously with a suspension (as seen in the example). Instead of RET, it is preferable to notate the intervallic pattern in the thoroughbass figures.