Inquiry-Based Music Theory OER Text Book

Harmonic functions

If a musical function describes the role that a particular musical element plays in the creation of a larger musical unit, then a harmonic function describes the role that a particular chord plays in the creating of a larger harmonic progression. Each chord tends to occur in some musical situations more than others, to progress to some chords more than others. These tendencies work together to create meaningful harmonic progressions, which can in turn form the harmonic foundation for musical phrases, themes, and larger formal units.

Generally speaking, the function of a chord concerns the notes that belong to it (its internal characteristics), the chords that tend to precede and follow it, and where it tends to be employed in the course of a musical phrase.

A theory of harmonic functions is based on three fundamental principles:

- Chords are collections of scale degrees.

- Each scale degree has its own tendencies.

- The collective tendencies of a chord’s scale degrees in combination is the chord’s function.

(Note the absence of root and quality from consideration here.)

Because tendency is style-specific, the same chord can have different functions in different musical styles. For instance, the kinds of functions we find in classical music are different from those we find in pop/rock songs from the Billboard charts. And though there are some general harmonic traits that are common to most eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Western composers (what we call the “common practice”), when we look in closer detail, we find some significant differences in the way Bach, Mozart, Brahms, and others compose their harmonic progressions.

Our initial exploration of harmonic functions will engage the general “common practice” that is shared by most eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Western composers. As we explore specific genres, composers, and works within that common practice, we will have opportunity to explore the more nuanced differences between composers, as well as to move beyond common-practice Western art music to include other styles, such as pop/rock.

The three common-practice harmonic functions

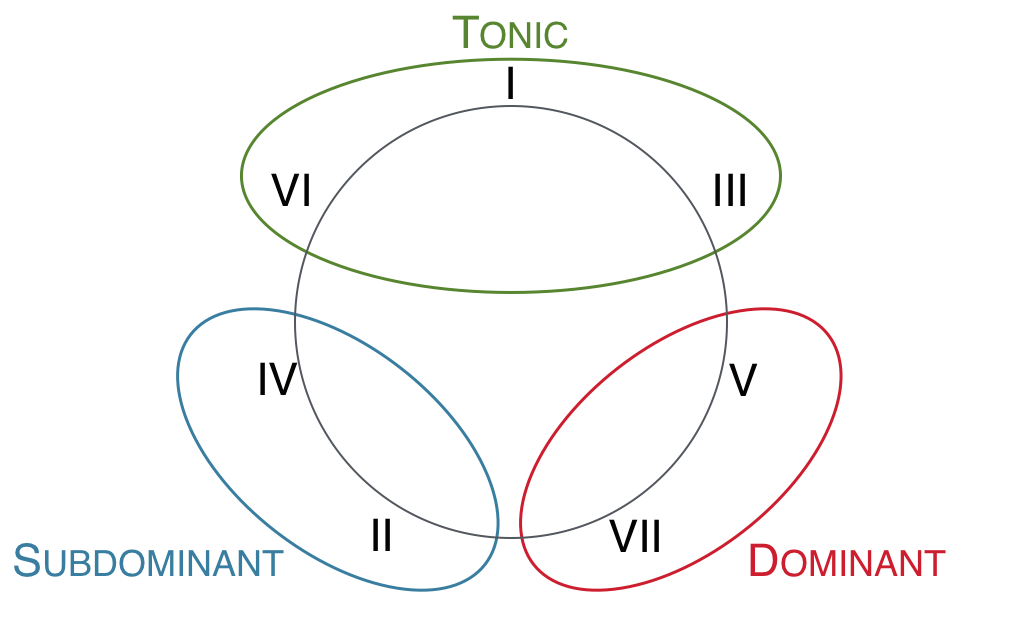

In common-practice music, harmonies tend to cluster around three high-level categories of harmonic function. These categories are traditionally called tonic (T), subdominant (S — also called predominant, P or PD), and dominant (D). Each of these functions has their own characteristic scale degrees, with their own characteristic tendencies. And each of these functions tend to participate in certain kinds of chord progressions more than others.

If you are already comfortable with Roman numerals, you can generally think of I, III, and VI as tonic, II and IV as subdominant, and V and VII as dominant. (Though, as you will see below, there is more to it than that.)

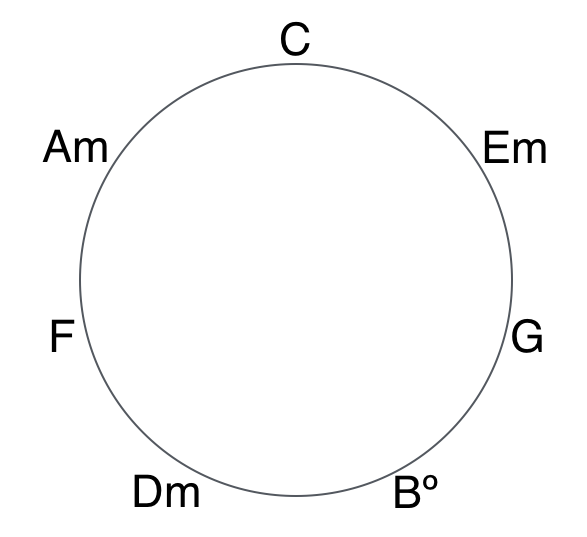

To visualize these functional categories, think of the usual triads in C major arranged on a circle of thirds. Note that each chord sits between the two triads that share the most tones in common — C major (C, E, G) sits between E minor (E, G, B) and A minor (A, C, E), both of which share two tones in common with C.

Convert these chords to Roman numerals (in C major), and we can see the functions. Since the function is determined by the tendencies of the tones that they share, and since on this graph chords are grouped together by notes they have in common, they are also grouped together by function.

Triads arranged on the circle of thirds, labeled by harmonic functions.

Interestingly, in common-practice music, a chord’s function can be determined solely by its internal characteristics (the notes that make up the chord). This is not true of all styles. For example, in pop/rock music a IV chord can exhibit very different functional tendencies depending on its context. But in classical music, simply knowing the notes in a chord is enough to determine its general harmonic function and the general tendencies of that chord and its individual notes.

The syntactic properties of these functions will be covered elsewhere. What follows simply explains how to determine the function of a chord in common-practice music with greater specificity.

Finding the function of a chord

Each of the three harmonic functions — tonic (T), subdominant (S), and dominant (D) — have characteristic scale degrees. Tonic’s characteristic scale degrees are 1, 3, 5, 6, and 7. Subdominant’s characteristic scale degrees are 1, 2, 3, 4, and 6. Dominant’s characteristic scale degrees are 2, 4, 5, 6, and 7.

Ian Quinn (a music theorist at Yale University) further distinguishes these scale degrees, using the categories of functional triggers, functional associates, and functional dissonances. These categories help us understand the functional properties of chords whose scale degrees belong to more than one function, as well as how certain notes behave within a chord. They also help us understand which scale degrees are more or less characteristic of a function ― something that will help determine function when a complete chord is not present.

| function | triggers | associates | dissonances |

|---|---|---|---|

| T | 1 and 3 | 5 and 6 | 5 (if 6 is also present) and 7 |

| S | 4 and 6 | 1 and 2 | 1 (if 2 is also present) and 3 |

| D | 5 and 7 | 2 | 4 and 6 |

In terms of moveable-do solfège:

| function | triggers | associates | dissonances |

|---|---|---|---|

| T | do and mi/me | sol and la/le | sol (if la/le is also present) and ti/te |

| S | fa and la/le | do and re | do (if re is also present) and mi/me |

| D | sol and ti/te | re | fa and la/le |

To determine the function of a chord, find the function that includes all the scale degrees of a chord (regardless of chromatic alterations ― that is, treat ♯4 the same as regular scale-degree 4). If more than one function contains all the scale degrees, take the function with the most triggers in the chord.

There is one exception to this (for now): a chord with scale degrees 6, 1, and 3 is a special kind of tonic chord, called a destabilized tonic. Quinn uses the special functional label is Tx, rather than simply T, for this chord.

Also note that because the III7 chord’s scale-degrees do not wholly belong to any of the three functions, it can behave similar to T and D chords, depending on context. It is a rare chord in its diatonic form.

This handout will help you determine the function of a chord from the bass scale degree and/or the Roman numeral.

Labeling chords

There are two ways in which we will label chords according to function. The first is to label chords with Roman numerals, thoroughbass figures, and functional labels. When doing so, place the appropriate Roman numeral below the bass line, the thoroughbass figure above the bass line (since it represents the upper voices), and place a functional label T/S/D below the Roman numeral (no Tx; simply call a VI chord T). For now this label can simply apply T, S, or D to individual chords; in the future, we will alter this practice slightly in order to show functional prolongation. The first example shows individual chord functions, and the second example shows functional prolongation.

The second way to label a harmonic progression is what Quinn calls functional bass. Functional bass symbols combine a chord’s function (T, S, D, or Tx) with an Arabic numeral denoting the scale degree of its bass note. A tonic chord with do in the bass is T1, a dominant chord with ti in the bass is D7, etc. If the bass note is chromatically altered, use a + or – to denote raised or lowered (la and ti in minor do not count, since le, la, te, and ti all belong to minor, but you can use +/– for clarity if you like). And if there is a chromatically altered note anywhere in the chord, put the functional bass symbol inside square brackets: [S6], [S+4], [T–7], etc. (See Chromatically altered subdominant chords, Applied chords, and Modal mixture for more information on common chromatically altered chords.)

Quinn also advocates using what I call interpreted functional bass. This nomenclature uses the same symbols, but uses parentheses to denote contrapuntal prolongation and lower-case postscripts to explain the contrapuntal role of the embellishing chord (p for passing, n for neighbor, i for incomplete neighbor, d for divider, e for embellishing — all of these refer to the voice-leading pattern in the bass voice). Following is an example of interpreted functional bass.

In this text, we primarily use the first method of Roman numerals and (prolonged) harmonic functions, since it is the most common in North American music theory. However, functional bass can be helpful for identifying categories of chords that belong together. For example, in a dictation or transcription task, we might hear re in the bass but not know what specific chord it is. If context tells us it is likely a dominant chord, rather than subdominant, we can label it D2. This rules out II (a subdominant chord) but keeps open multiple dominant options like V6/4 or VII6 until we are able to make a final determination. Similarly, when composing, there are patterns that might take an S4, with the specific chord (IV or II6) determined by voice-leading rather than harmonic syntax, but where a D4 chord (V4/2) would be syntactically inappropriate, regardless of voice-leading.

Thus, when referring to specific chords, we will use Roman numerals to label the chords and functional labels to interpret their role in context. When referring to broader categories of chords, we will more often use functional bass.