Inquiry-Based Music Theory OER Text Book

Classical cadence types

A cadence is a point of arrival that punctuates the end of a musical unit, such as a phrase, theme, large formal section, or movement. A cadence is at once a harmonic, melodic, rhythmic, and formal event, but cadences tend to be grouped according to different ways in which harmony and melody articulate that point of arrival.

Authentic and half cadences

These unit-ending points of arrival are first grouped into authentic cadences and half cadences. An authentic cadence occurs when a formal unit ends with the progression D5–T1 (V(7)–I, sol to do in the bass voice). If the melody accompanying this harmonic progression arrives on do, it is called a perfect authentic cadence; it the melody ends on mi or me (or more rarely sol), it is called an imperfect authentic cadence.

Phrases that end on V without progressing to I are called half cadences. These cadences typically contain re in the melody, though ti and sol are also possible points of melodic arrival. The V is almost invariably a triad, rather than a seventh chord, and it is always in root position (D5).

Differentiating between perfect authentic cadences (PAC), imperfect authentic cadences (IAC), and half cadences (HC) by ear and with a score is essential both to formal analysis and model composition.

Simple, compound, and double cadences

Writers of Italian keyboard treatises like Furno and Fenaroli (and, more recently, American historical theorists like Robert O. Gjerdingen) differentiate cadences according to the voice-leading found over the dominant harmony. These distinctions do not replace the above PAC/IAC/HC distinctions; rather they add another level of detail that is particularly helpful in model composition. These voice-leading distinctions provide three more cadence categories to complement PAC, IAC, and HC: the simple cadence, the compound cadence, and the double cadence.

A simple cadence occurs when the dominant harmonic function is articulated by a single chord—either a triad or a seventh chord. The simple cadence can be used in a PAC, IAC, or HC construction, though the seventh-chord version is typically only found in authentic cadences.

A compound cadence occurs when the bass note sol of the cadential dominant is repeated, often with the second sol an octave lower than the first. The compound cadence comes in three specific forms.

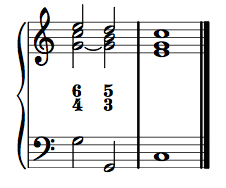

The first type of compound cadence involves a 4–3 suspension—do to ti—over the sol bass of the dominant harmony. In a four-voice texture, the other two voices sustain a fifth above the bass and an octave above the bass. The thoroughbass figure is typically the abbreviated 4–3, which stands for 8/5/4–8/5/3 in four voices. The 4–3 suspension can occur over the cadential dominant of a PAC, IAC, or HC.

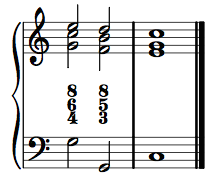

The second type of compound cadence adds a mi/me to re voice (6–5) to the above 4–3 suspension. In a four-voice texture, the bass is doubled. The typical thoroughbass figure is 6/4–5/3, leading to the common name for this progression, the cadential six-four. The complete figure is 8/6/4–8/5/3. The cadential six-four can occur over the cadential dominant of a PAC, IAC, or HC.

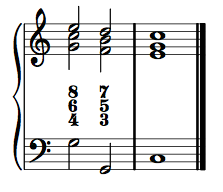

The last type of compound cadence is a special case of the cadential six-four, where the fourth voice introduces a seventh over the second dominant chord, rather than simply doubling the bass for both chords. This compound cadence type requires four voices and complete thoroughbass figures of 8/6/4–7/5/3. This figure rarely occurs over the dominant of a half cadence and is instead reserved primarily for authentic cadences.

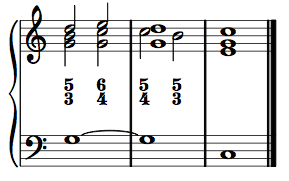

A double cadence is a four-stage pattern over the cadential dominant used almost exclusively in perfect authentic cadences. Though it had expired from common use by the time of Mozart and Haydn, it was a staple for earlier galant composers and Classical treatises on composition and accompaniment. The four-stage pattern over the dominant is 5/3–6/4–5/4–5/3. In four voices, the bass is also doubled, or a seventh can be applied to any chord of the fifth (i.e., not the 6/4).

Voice-leading in strict keyboard style

In strict melodic keyboard style, always end an idealized phrase with a perfect authentic cadence (PAC). Approach the melody’s final do by step whenever possible, from re or ti, preferably from re. When using compound or double cadences, use the orientation of upper voices shown in the above figures (transposed to the appropriate key, of course).

In basso continuo style, the top voice can end with any member of the tonic triad. As much as possible, use the voices provided in the figures above, but invert them (move the tenor line to the top, making the melody and alto the alto and tenor, for example). Simply make sure that if ti occurs in the top voice before the final tonic chord, it resolves its tendency up to do.

In either case, pay special attention to the cadential six-four version of the compound cadence. Despite forming a consonant triad with the bass, both the sixth and the fourth of the first chord act like suspensions, and therefore must resolve down by step and be prepared smoothly (by common tones or steps). This is true no matter which part is in the melody, alto, or tenor.