Inquiry-Based Music Theory OER Text Book

Lesson 1a - Pitches and Clefs

Class Discussion

Given that the class is already familiar with note names and staff notation, the discussion of identifying pitches on clefs was a brief, simple dictation of the note names divided into lines and spaces for each clef. They were:

The discussion of the secondary name for each clef – particularly the treble clef as a G-clef – prompted various suggestions. For the treble clef, one student suggested that the clef is a stylized G and another pointed out that the clef encircles the G on the second line of the staff. Both of these are correct.

This led immediately immediately to the quick assumption that the F-clef uses its “dots” to enclose the F on the fourth line of the staff, and the C-clefs have an “arrow” that points to C at all times. This arrow points to different lines for both alto and tenor clef.

For a well-researched, short article on the evolution of clefs, I suggest reading Jimmy Stamp’s The Evolution of the Treble Clef from the Smithsonian website.

The tips and tricks for mastering clefs could be broken into three categories:

- Memorization - The most widely used method uses flash cards or other repetitive devices to practice identifying notes on each clef to ensure a quick and efficient memorization.

- Relative note identifications - Another student remembers one important note for each clef and then visually “counts” through the alphabet upward or downward to find pitches in unfamiliar clefs. One student suggested remembering where C is and counting by steps (letter names), but another suggested memorizing how thirds are stacked to move around more quickly. While this is a fine method for beginning to familiarize yourself with clefs, it will ultimately be too slow and inconsistent to be practical.

- The final suggestion was to determine the relationship of your weaker clefs to your strongest clef, and then use this to read in the clef. For example, if you are primarily comfortable in treble-clef, you could remember that alto-clef moves all of the pitches down by a step relative to treble clef. (This ignores octave displacement, of course.) In this case, if you read the alto clef as a treble clef but up a step, this compensates and gives you a quick visual method for reading the clef. Like the relative note identification method above, this could be slow or inconsistent, but if one regularly transposes, this could be used.

Further Reading

From Open Music Theory

Notes

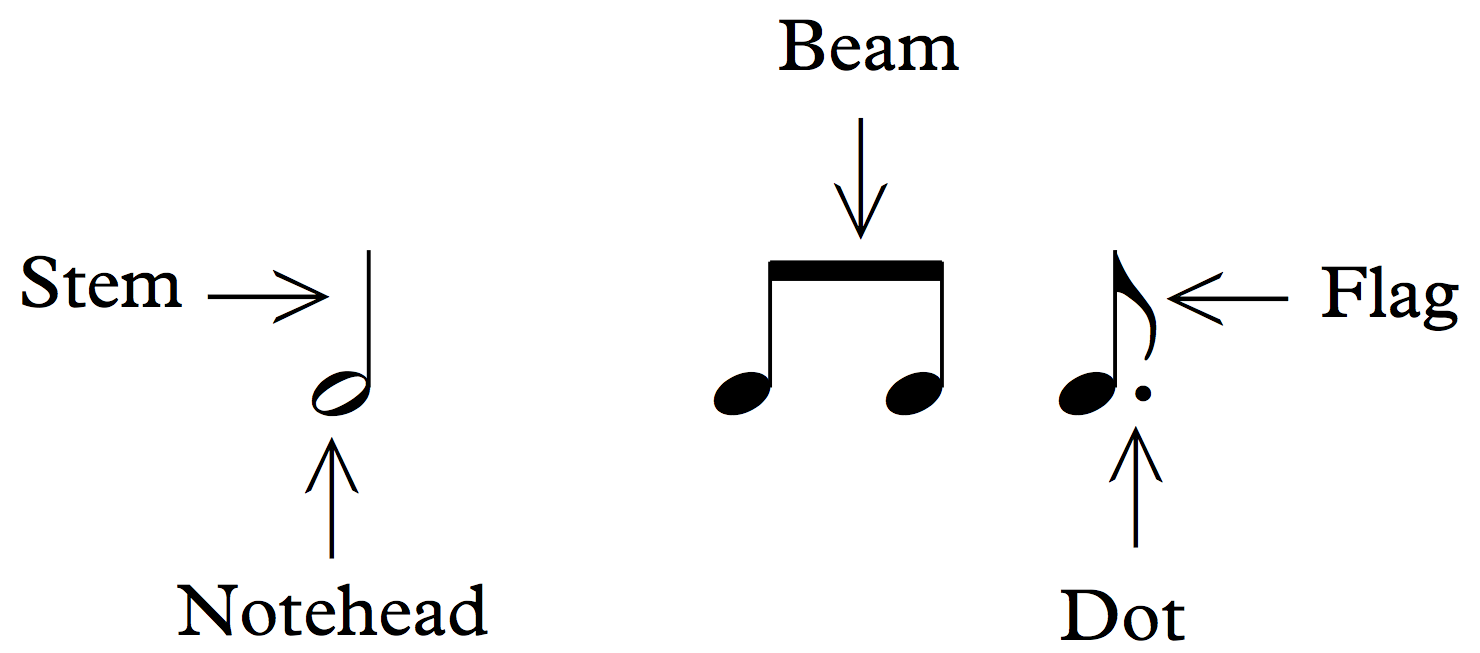

When written on a staff, a note indicates a pitch and rhythmic value. The notation consists of a notehead (either empty or filled in), and optionally can include a stem, beam, dot, or flag.

Staff

Notes can’t convey their pitch information without being placed on a staff. A staff consists of five horizontal lines, evenly spaced. The plural of staff is staves.

Clefs

Notes still can’t convey their pitch information if the staff doesn’t include a clef. A clef indicates which pitches are assigned to the lines and spaces on a staff. The two most commonly used clefs are the treble and bass clef; others that you’ll see relatively frequently are alto and tenor clef.

Grand staff

The grand staff consists of two staves, one that uses a treble clef, and one that uses a bass clef. The staves are connected by a curly brace. Grand staves are used frequently for notating piano music and other polyphonic instruments.

Ledger lines

When the music’s range exceeds what can be written on the staff, extra lines are drawn so that we can still clearly read the pitch. These extra lines are called ledger lines. In the example below, From Haydn’s Piano Sonata in G (Hob. XVI: 39), A-flat5 occurs just above the treble staff in the right hand, and G3 and B3 occur just below the treble staff in the left hand.

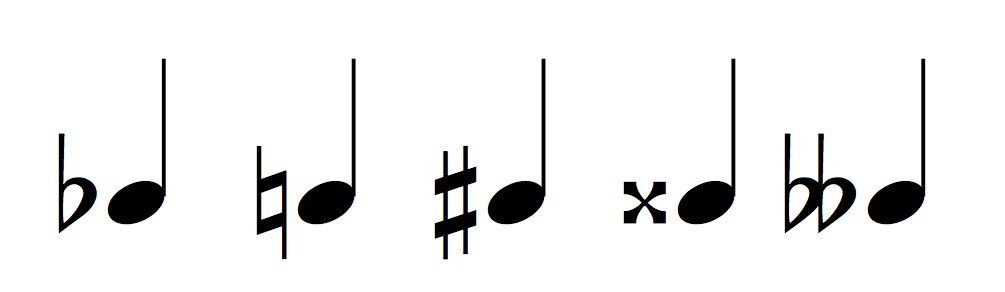

Accidentals

Accidentals are used to indicate when a pitch has been raised or lowered. They are written to the left of the pitch.

- When you lower one of the white notes of the piano by a semitone, you add a flat.

- When you raise one of the white notes of the piano by a semitone, you add a sharp.

- When you raise a note that is already flat by a semitone, you add a natural.

- When you lower a note that is already flat by a semitone, you add a double flat.

- When you raise a note that is already sharp by a semitone, you add a double sharp.

The example below shows the symbols for flat, natural, sharp, double sharp, and double flat, respectively.