Inquiry-Based Music Theory OER Text Book

Lesson 2b - Scales and Scale Degrees - Diatonic, Pentatonic, and Chromatic

Class discussion

To begin our discussion, I asked for definitions of music. The first definition offered was:

Music is organized sound.

This is possibly the most succinct explanation that differentiates music from sound and/or noise. It also provides a great launching point for discussing pitch collections and scales. If we accept that music is “organized sound”, then the method used to organize it will define any style of composition. For this course, we will be studying tonal music, because tonal describes the organizational method of this music.

Tonal music is organized around a central tone called the tonic.

Once we have chosen a central pitch around which we build a tonality, every pitch in the tonality can be summarized by its relationship to that pitch. It is these intervallic relationships that create pitch collections, and if that pitch collection has certain properties, it can be further categorized.

For the majority of this course, we will be discussing diatonic music which is a subset of tonal music. The term diatonic can have a variety of meanings depending on context, but for this course, we will be using this term to refer to music that:

- is built around a tonic

- includes all seven pitch names (i.e. letters)

- has a specific order of intervals that create a scale

Put simply, our musical hierarchy is:

- Music - organized sound

- Tonal music - music organized around a central pitch

- Diatonic music - tonal music that uses all seven letter names only once and follows a specific order of intervals

- Scale - a condensed ordering of all seven pitches in a diatonic pitch collection where all intervals are either minor 2nds or major 2nds

- Diatonic music - tonal music that uses all seven letter names only once and follows a specific order of intervals

- Tonal music - music organized around a central pitch

Scales

In diatonic music, each scale has seven pitches. All seven letters can be used once, and no letter can be used more than once. This creates a series of 2nds, and it is the alternation of major 2nds (whole-steps) and minor 2nds (half-steps) that create our scale.

Major scales have an intervallic pattern of:

(W = whole-step, H = half-step, A = augmented 2nd)

W - W - H - W - W - W - H

Natural minor scales have an intervallic pattern of:

W - H - W - W - H - W - W

Harmonic minor scales have an intervallic pattern of:

W - H - W - W - H - A - H

Melodic minor scales have both an ascending and descending form. The descending melodic minor intervallic pattern is identical to a descending natural minor scale. (The necessity of this seemingly redundant pattern is discussed below under “Why we need three minor scales”.) The ascending melodic minor intervallic pattern is:

W - H - W - W - W - W - H

Scale degrees

When discussing scales, it is helpful to have a way to refer to pitches that does not reference the particular key. For example, the first “Happy Birthday” example on the previous page is written in G major, but there are eleven other keys in which we could write that melody. In order to reference the interval pattern rather than the actual pitches, we use scale degrees.

The most common way to communicate pitches of the scale is to use scale degree numbers. We denote these by placing a caret ^ above the scale degree number. For example, the pitch that is a fifth above the tonic would be called fifth scale degree and would be written as ^5, although the caret would be above the numeral,not to the side.

Another traditional method is to use the names of the functions of each pitch as it relates to tonic. These names evolved over centuries of theory treatises from scholars such as Rameau, Riemann, Secther, Schoenberg, and Schenker. We will not use these names often in this course, but knowing them can help understand harmonic function when that concept is introduced.

They are:

- Tonic

- Supertonic

- Mediant

- Subdominant

- Dominant

- Submediant

- Leading-tone/Subtonic

Notice the relationship between any term and its counterpart as denoted by the prefix sub. The dominant is a fifth above the tonic; the subdominant is a fifth below the tonic. The mediant is a third above the tonic; the submediant is a third below the tonic.

The supertonic is a 2nd above the tonic, but because of the importance and function of the leading-tone, the scale degree names changes to reflect the difference between a major 2nd below the tonic versus the minor 2nd below the tonic. If the 2nd below the tonic is a whole-step, we call it the subtonic. If the 2nd below the tonic is a half-step, we call it the leading-tone. This is true in both major and minor.

Tonal centers and modes

We consider a key to be defined by its tonic, so if two scales share a tonic, they are considered to be the same key but different modes of each other. For example,G major and G minor are the same key, but different modes.

Why we need three minor scales

Most intermediate music students understand that they must learn different forms of the minor scale, but they do not often give much thought as to why.

Natural minor is the most obvious. It uses all of the naturally occurring notes from the key signature.

We will discuss the role of harmonic minor more when we begin analyzing chords, but as the name implies, it is a form of minor that emphasizes the most common scale degrees from a harmonic standpoint.

However, the “Happy Birthday” examples from the previous page are perfect for exploring the imoprtance of melodic minor. By keeping the interval sizes from “Happy Birthday” but changing the pitches to fit the various forms of minor, I created three similar but distinct versions of “Happy Birthday”. When the class listened to the natural minor version, they felt that the first te did not work with the tune. In the harmonic minor version, the augmented 2nd that occurs between ti and le surprised them and “felt wrong”. Finally, the melodic minor version sounded entirely correct (although one student didn’t like the depressing change to a happy song…)

This easily highlighted the role of melodic minor – to create melodies in minor. By having both an ascending and descending version, we can resolve the sixth and seventh scale degrees upward and downward by relying on the tendency of those scale degrees. Te and le both have a strong downward pull and almost always resolve downward. Ti and la both have a strong upward pull and tend to resolve upward. These are general rules and are occasionally broken, but I encourage you to play with the example below to hear how “strange” the piece becomes if you do not allow the sixth and seventh scale degrees to account for their resolutions. (Try putting la in for every sixth scale degree for the most obviously jarring version.)

Pentatonic Scales

The pentatonic scale is a nearly universal sonority as demonstrated by Bobby McFerrin in the following clip.

Neither the major or minor form of the pentatonic scale relates strongly to the harmonic functions that we will study in this course, but their prominence in world and folk musics makes them an important part of our musical heritage. This alone justifies familarity with these colors.

Major and minor pentatonic scales have a simple relationship to their major and minor counterparts. The major pentatonic scale uses the first, second, third, fifth, and sixth scale degrees of the major scale. The minor pentatonic scale uses the first, third, fourth, fifth, and seventh scale degrees of the minor scale.

Even though they do not function diatonically, there are two general concepts of harmony in pentatonic scales.

- The tonic and dominant scale degrees still function as the primary harmonic “poles” in a pentatonic scale.

- The lack of a leading tone in both forms is the primary reason that these do not function similarly to diatonic harmony. That being said,

lain major pentatonic scales andtein minor pentatonic scales can take on a similar function by pulling toward the tonic in a melody.

Chromatic scale

The chromatic scale is not a tonality, because it has no tonic. It is however, the ultimate pitch collection and functions as a useful way to familiarize a student with all twelve pitch-classes.

The final “Happy Birthday” version on the previous page uses every possible scale degree in order to demonstrate resolution in a diatonic key, but it is not a “chromatic” tonality. That example is still in G major, but it is heavily embellished using chromatic tones.

Of particular note, the example demonstrates the importance of considering resolution when choosing which chromatic pitch to use. Generally, if a pitch is raised, it should resolve upward; if a pitch is lowered, it should resolve downward. For example, li and te are enharmonically equivalent, but they function differently because their accidentals imply specific resolutions. Li should resolve to ti, but te should resolve to la. This is not only important in simplifying notation for harmonic analysis, but it also makes it easier for performers when reading heavily chromatic music.

Putting it all together

If we were to put attach all of these ideas to staff notation, we get:

Further Reading

From Open Music Theory

A scale is a succession of pitches ascending or descending in steps. There are two types of steps: half steps and whole steps. A half step (H) consists of two adjacent pitches on the keyboard. A whole step (W) consists of two half steps. Usually, the pitches in a scale are each notated with different letter names, though this isn’t always possible or desirable.

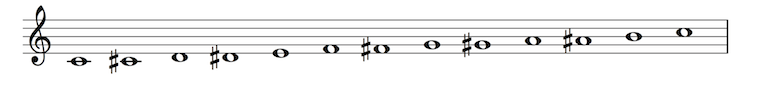

The Chromatic Scale

The chromatic scale consists entirely of half steps, and uses every pitch on the keyboard within a single octave. Here is the chromatic scale that spans the pitches C4 through C5.

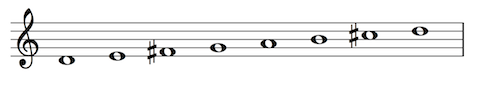

The major scale

A major scale, a sound with which you are undoubtedly familiar, consists of seven whole (W) and half (H) steps in the following succession: W-W-H-W-W-W-H. The first pitch of the scale, called the tonic, is the pitch upon which the rest of the scale is based. When the scale ascends, the tonic is repeated at the end an octave higher.

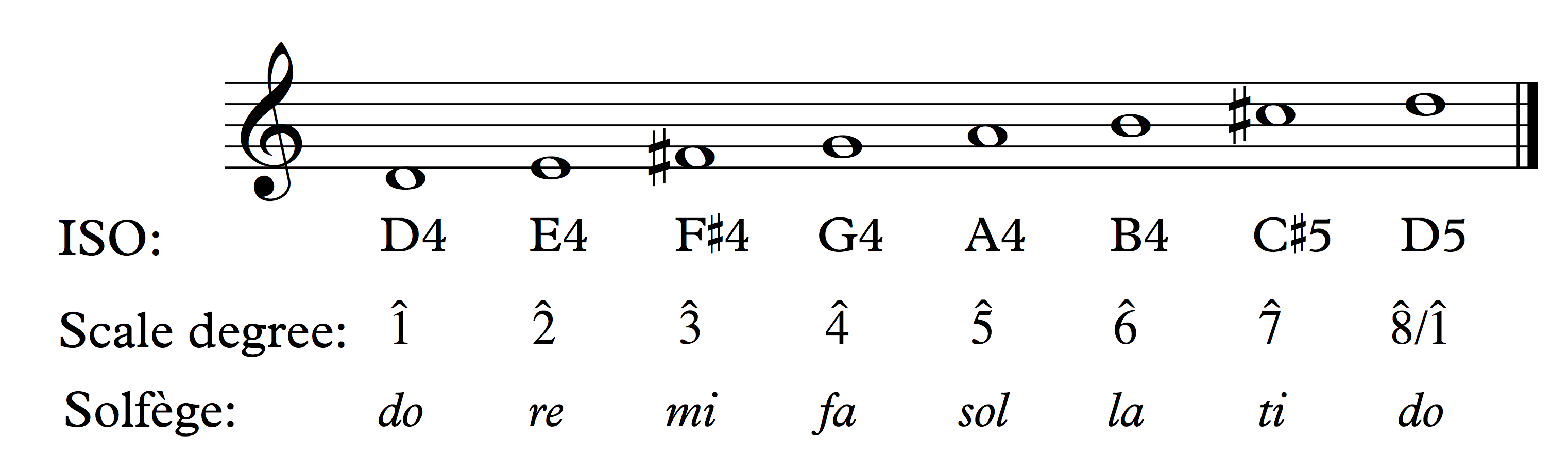

Here is the D major scale. It is called the “D major scale” because the pitch D is the tonic and is heard at both ends of the scale.

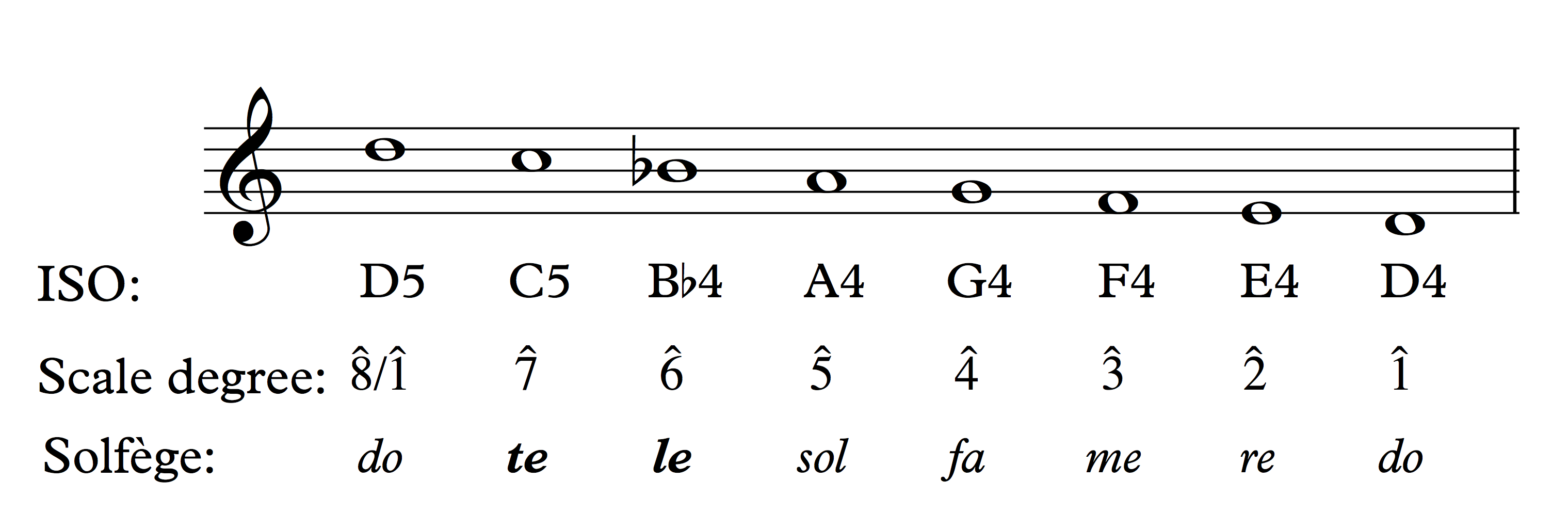

Scale degrees and solfège

While ISO notation allows us to label a pitch in its specific register, it is often useful to know where that pitch fits within a given scale. For example, the pitch class D is the first (and last) note of the D-major scale. The pitch class A is the fifth note of the D-major scale. When described in this way, we call the notes scale degrees, because they’re placed in context of a specific scale. Solfège syllables, a centuries-old method of teaching pitch and sight singing, can also be used to represent scale degrees (when used in this way, this system is specifically called movable-do solfège).

Scale degrees are labeled with Arabic numerals and carets (^). The illustration below shows a D-major scale and corresponding ISO notation, scale degrees, and solfège syllables.

The minor scale

Another scale with which you are likely very familiar is the minor scale. There are several scales that one might describe as minor, all of which have a characteristic third scale degree that is lower than the one found in the major scale. The minor scale most frequently used in tonal music from the Common Practice period is based on the aeolian mode (you’ll read more about modes later), which is sometimes referred to as the natural minor scale.

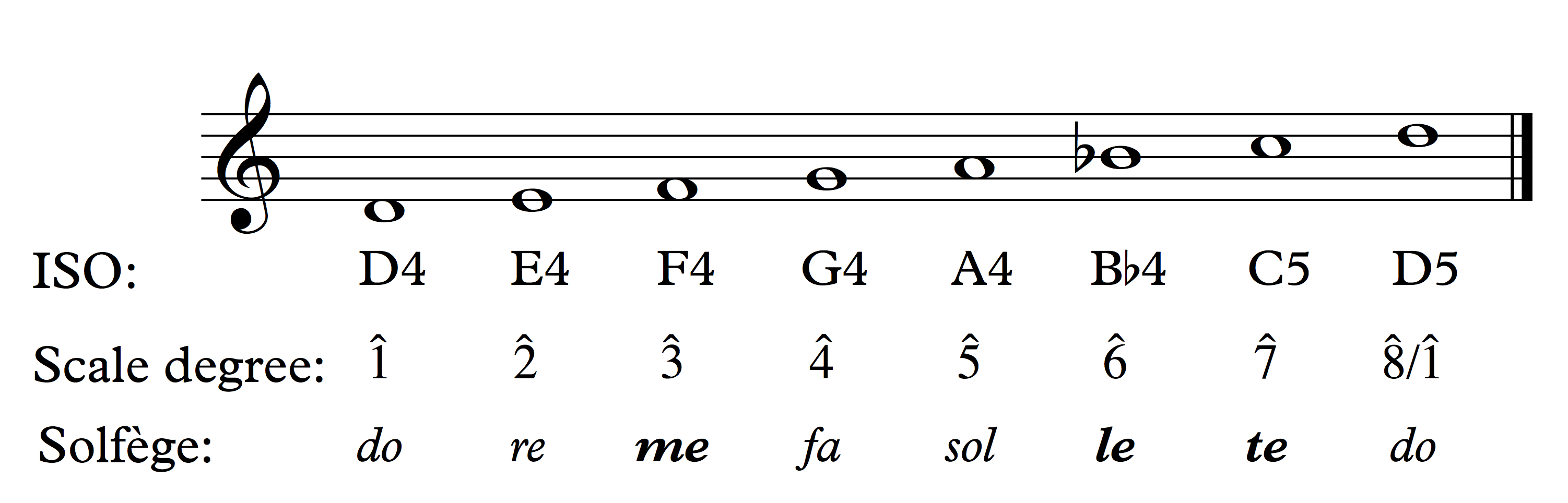

The natural minor scale consists of seven whole (W) and half (H) steps in the following succession: W-H-W-W-H-W-W. Note the changes in solfège syllables.

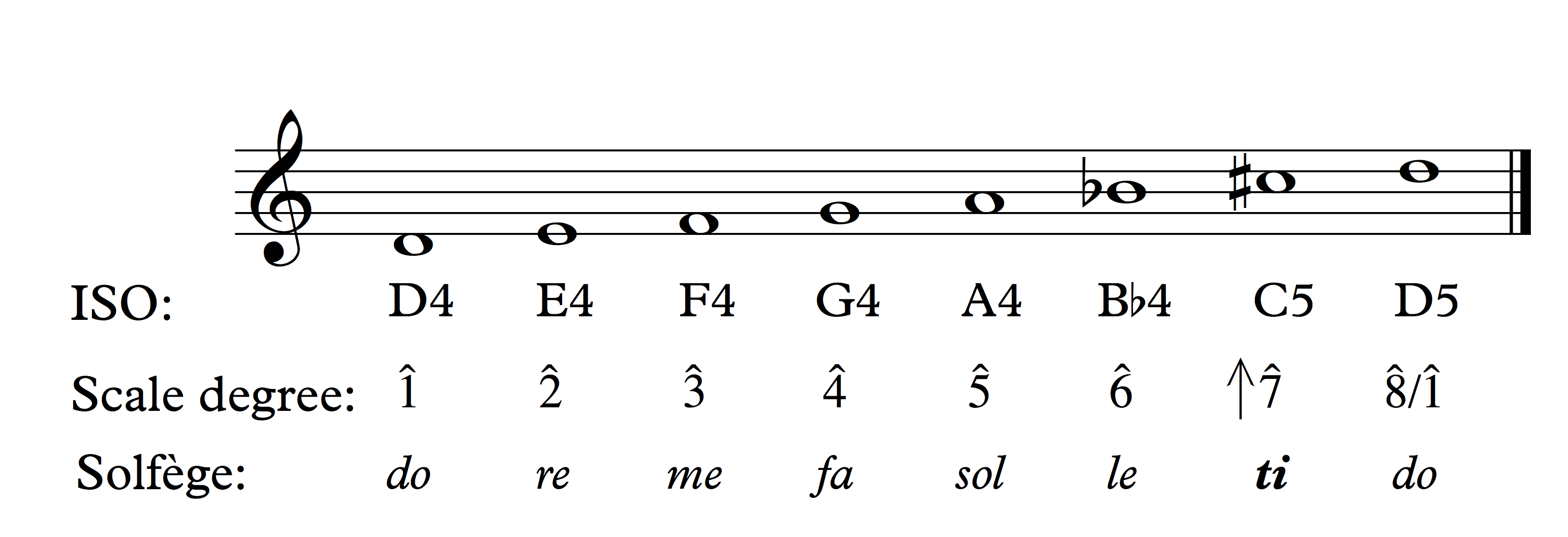

If you sing through the above example, you’ll notice that the ending lacks the same sense of closure you heard in the major scale. This closure is created in the major scale, in part, by the ascending semitone between ti and do. Composers often want to have this sense of closure when using the minor mode, too. They’re able to achieve this by applying an accidental to the seventh scale degree, raising it by a semitone. If you do this within the context of the natural minor scale, you get something called the harmonic minor scale.

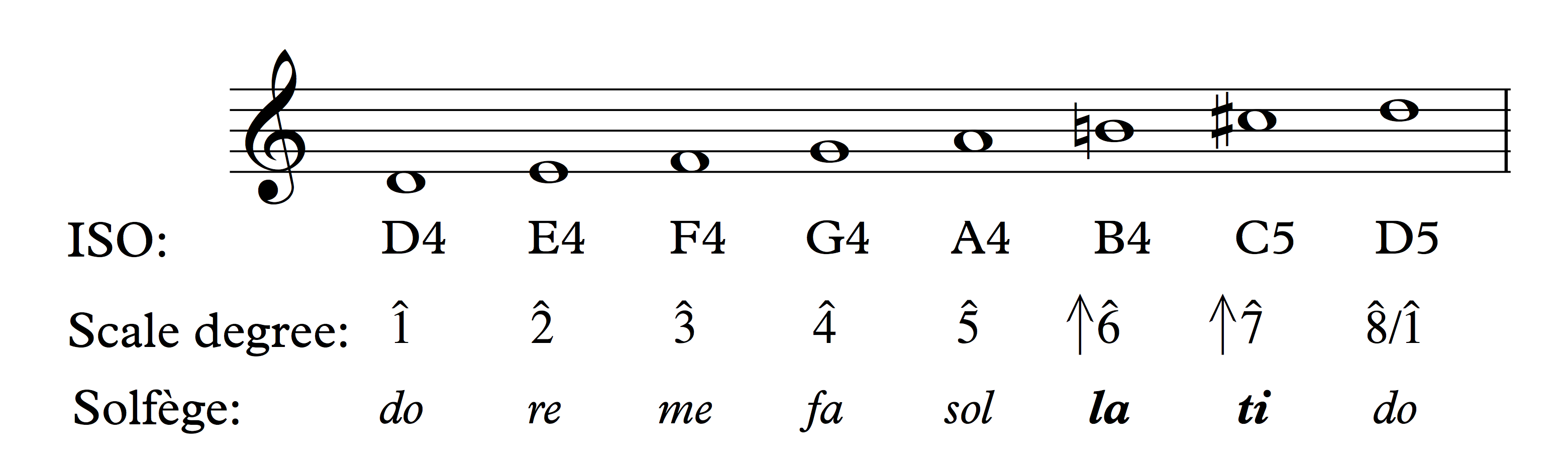

Now the last two notes of the scale sound much more conclusive, but you might have found it difficult to sing le to ti. When writing melodies in a minor key, composers often “corrected” this by raising le by a semitone to become la when approaching the note ti. When the melody descended from do, the closure from ti to do isn’t needed; likewise, it is no longer necessary to “correct” le, so the natural form of the minor scale is used again. Together, these different ascending and descending versions are called the melodic minor scale.

When ascending, the melodic minor scale uses la and ti.

When descending, the melodic minor scale uses the “natural” te and le.

Truth be told, most composers don’t really think about three different “forms” of the minor scale. The harmonic minor scale simply represents composers’ tendency to use ti when building harmonies that include the seventh scale degree in the minor mode. Likewise, the melodic minor scale is derived from composers’ desire to avoid the melodic augmented second interval (more on this in the intervals section) between le and ti (and some chose not to avoid this!). In reality, there is only one “version” of the minor scale. Context determines when a composer might use la and ti when writing music in a minor key.