Inquiry-Based Music Theory OER Text Book

Lesson 6b - Voice-leading Considerations in Chorale-style Harmony

Class discussion

Implied harmony in two-parts

After some discussion, the class agreed that all of the two-voice counterpoints in the first example implied harmonies of V moving to I in the key of C major. The bass movement of the first three measures highlighted this, but even when the bass movement changed, the class still heard the same progression of V to I. From this, we drew the conclusion that two lines – in this case the soprano and bass lines – are enough to imply tonality. One student also pointed out that the chordal fifth was the least common chordal member in these examples, and as we will see when we begin voicing four-part harmony, the chordal fifth is indeed expendable. The root and third are best at implying a triad, and the seventh is obviously necessary to create a seventh chord.

The last bit of discussion on the first example revolved around the strength of cadences. There was no general concensus amongst the class about an absolute ranking, but in general, bass movement was a key factor in strength. For example, measures 1 and 3 were considered to be much stronger than the last measure. The last measure not only lacked sol to do in the bass, it also did not have a tonic in the final chord.

Non-Chord Tones in Cadential Motion

As we first begin to study non-chord tones, the most important thing to remember is what the name “non-chord tone” emphasizes. NCTs must not belong to the chord. The first four measures added decorations that were simply part of the V or V7 chords that were already implied. Of note, all students heard the added F in measures 3 and 4 as changing the harmony from V to V7, meaning that the harmony was altered rather than embellished.

Measure 5 continued this idea, but for teaching purposes, I asked them to consider this strictly as a triadic V chord. What does that make the F? Of course, it becomes a non-chord tone called a passing tone. A passing tone is approached by step and left by step in the same direction.

One astute student then asked what would happen if we applied the same logic to measures 3 and 4. This was admittedly beyond the scope of what I intended to cover, but because we had briefly discussed the idea of the term appogiatura to describe a melodic shape when discussing second species counterpart, I admitted that if the F was considered to be a non-chord tone, both measures 3 and 4 would be considered to have a non-chord tone of an appogiatura. An appogiatura is a non-chord tone that is approached by leap and then left by stepwise motion in the opposite direction.

The final measure clearly contained an NCT, because the A could not be incorporated into a V or V7 chord. This is an example of a neighbor tone: a non-chord tone that is approached by step and left by step in the opposite direction.

My final reminder to students when looking for non-chord tones: Always make sure that the pitch is not actually a chord tone! This is one of the most common mistakes for beginning analysts.

Suspensions

After looking at the examples for suspensions, the first suggestion was that a suspension is a pitch that is tied over from the previous chord. This is on the right track, but defining a suspension requires considerably more information. The first and most easily dispelled misconception is that it must be tied; the tone can be re-articulated. From this point, the class was able to come up with three basic ideas for a full definition of a suspension:

- It must start as a chord tone in the previous chord

- It must be carried into the following chord and create a non-chord tone at the beginning of the chord.

- It must then resolve down by step to a chord tone in the new chord.

These three ideas directly relate to the standardized terminology for the three basic components of a suspension:

- Preparation - A chord tone that occurs as part of a separate chord before the suspension.

- Suspension - A non-chord tone that occurs at the moment that all other voices change to the new chord. This tone must be carried over from the previous chord, but it can be re-articulated.

- Resolution - The non-chord tone then resolves downward by step to a chord tone.

There are many common mistakes when creating or analyzing suspensions:

- There must be two chords. You cannot have a suspension with only one chord.

- It must resolve downward. If it resolves upward, it is a different kind of NCT.

- It must resolve by step.

Once you have familiarized yourself with these three concepts, review the examples on the previous page to ensure that you understand the form of a suspension. While doing this, you will notice that each of the suspensions is labeled with a pair of numbers in addition to the word sus. The class easily figured out that the numbers correspond to the intervals created by the suspension and its resolution against the bass. It is important to remember the difference between the terms root and bass. The root of the chord may be in a higher voice, but you will still measure the suspension against the bass. Always use the bass! The most common suspensions are the 4-3, 7-6, and 9-8 suspensions, but others can exist.

If the suspension is in the bass voice, you must measure the suspension against the most dissonant voice – this always creates a 2-3 suspension. There are two important things to notice here:

- The intervals go from small to large (2-3), but when the suspension is in an upper voice, the intervals go from large to small. This is because suspensions always resolve down by step. When you measure a downward resolution against a lower voice, the intervals get smaller as the upper voice moves closer to the bass. When you measure a downward resolution against a higher voice, the intervals get larger as the bass moves away from the upper voice.

- Assuming that there are more than two voices, there will always be a second and a third present above a suspension in the bass. We say that you measure it against the most dissonant interval, but the reality is that it is always a 2-3 suspension if the suspension is in the bass.

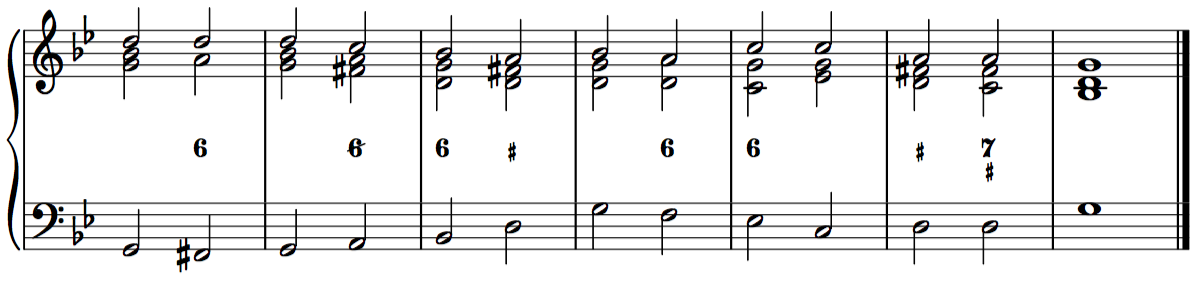

Adding inner voices

To this point, everything that we have discussed has been based on a two-voice model, but to move into full diatonic harmony, we need to add inner voices and fully flesh out the harmonies. When doing this, there are certain rules that create better voice-leading and voicings when followed, but please note that these rules are generally strong suggestions rather than hard and fast rules. Good composers constantly bend or break these rules if it better serves their ideas.

Doubling

When voicing triads in four-part harmony, at least one note must be doubled.

- Doubling the root is the ideal choice.

- Doubling the fifth is the second best option.

- Doubling the third is generally unacceptable, although there are certain corner cases in which this can be necessary. As a rule of thumb, try to never double the third. The reason for this will be clear after we talk about chordal resolutions in Unit 7a.

- If you need to omit a voice, the fifth is the only option, because the root and third are required to define the chord. Diminished triads are the only diatonic harmony that require a fifth as well.

- You can triple the root if necessary, but this creates a difficult voicing to continue writing afterwards. This is most commonly used as an ending chord of the piece (often after a V7).

Doubling in a seventh chord is similar, but because you have four notes for four voices, there is less freedom.

- There must always be a root, third, and seventh in the chord, because without any of them, the chord is no longer a functioning seventh chord.

- If necessary, you can omit the fifth.

- If the fifth is ommitted, the root is the only chord tone that can be doubled. Never double the third or the seventh.

Spacing

Spacing is a relatively straightfoward idea, but it took the class quite a few tries to come up with working definitions based on the examples. The final conclusions were:

- The bass can be as far from the tenor as needed.

- Tenor and alto cannot have more than an octave between them.

- Soprano and alto cannot have more than an octave between them.

- Tenor and soprano can have more than an octave between them.

- When the tenor and soprano are within an octave of each other, we call this a closed voicing.

- When the tenor and soprano are more than an octave apart, we call this an open voicing.

In general, a good voicing will mimic the overtone series on which our harmony is created. This details of this concept are discussed in Unit 8, but a general rule of good voicing is to allow wider intervals between lower voices and narrower intervals between high voices.

Range

The ranges for each voice in the examples are conservative, but will serve us well in our beginning part-writing. These are highly dependent on the intended performers.

Voice-crossing

There was no easy way to notate this in the examples, but voice-crossing should be avoided unless absolutely necessary. It is almost never absolutely necessary.

Further reading

From Open Music Theory

Chord voicing

In strict keyboard-style writing, there are four voices: the bass line (which is usually a given in basso continuo style), and three upper voices: the melody or soprano, the alto, and the tenor (from highest to lowest). Since all three upper voices must be played by a single hand, they should never span more than an octave.

The melody always has an upward-pointing stem. Alto and tenor share a downward-pointing stem. If the alto and tenor share a note, that note receives a single downward-pointing stem. (See m. 1 of the example below.) If melody and alto share a note, that notehead is double-stemmed. (See m. 4 of the example below.)

When choosing the notes to place in the upper voices above a figured bass, use the bass and figures to determine the pitch classes present in the chord. (When realizing an unfigured bass, you must determine appropriate figures before realizing.) If the chord is a four-note chord, use each chord member once, including the bass (exceptions will be noted later). If a chord has three pitch-classes (a triad, for instance), use each pitch-class once, and “double” one of them according to the following principles:

- If the figure is 6/4, 5/3, or other chord of the fifth, double the bass pitch class.

- If the figure is 6/3 and the bass is a fixed scale degree (do, re, fa, or sol), double the bass pitch class.

- If the figure is 6/3 and the bass is a variable scale degree (mi/me, la/le, or ti/te) or a chromatically altered pitch, double one of the upper voices at the octave or unison.

- Generally, do not double a variable scale degree or a chromatically altered pitch.

Tendency tones

A tendency tone is a pitch (class)—usually represented as a scale degree—that tends to progress to some pitch classes more than others. Sometimes this tendency is absolute within a style, but more often it is context-dependent.

The most prominent tendency tones in Western tonal styles are ti (not te) and le (not la).

Generally speaking, when ti appears it tends to be followed by do in the same voice. In a harmonic context, this tendency is strongest when ti occurs in a dominant-functioning chord, and the “resolution” of that tendency comes upon change of function (to tonic or predominant).

Likewise, when le appears, it tends to be followed by sol in the same voice. This tendency is less dependent on function.

Exceptions to these tendencies include:

- When ti is in the middle of a stepwise descent (re–do–ti–la–sol, for example), it can progress down by step. (Note that step inertia here diminishes the effect of an “unresolved” tendency tone. Because there are two conflicting tendencies in play, in this case, either can be “resolved” unproblematically.)

- When ti is in an inner voice, it can progress down to sol if necessary to accomplish good voice-leading in the other voices and ensure complete chords. This is called a frustrated leading-tone.

- When ti is a functional dissonance of a tonic-functioning chord (see below) it should progress down by step.

Functional dissonances

Some tendencies, such as the tendency for le to progress down, are relatively context-independent. Others are heavily contextualized. The primary contextual tendency for how melodic notes progress is the concept of functional dissonance.

Keep in mind from the Harmonic functions resource that chords tend to cluster in one of three functional groups (T, P, or D) When pitches fuse into a chord expressing one of these three functions, the pitches that comprise that have certain tendencies of progression that they may or may not have in other contexts.

Following are the scale degrees which act as dissonances for their respective functions:

| function | dissonances |

|---|---|

| T or Tx | 7, 5 when 6 is also present |

| P | 3, 1 when 2 is also present |

| D | 4, 6 |

In purely diatonic music (triads and seventh chords, no chromatics), these will include the seventh of every seventh chord, the fifth of viiº or VII (fa), and the fifth of III or iii (ti/te).

Keep in mind that only sometimes do these functional dissonances express themselves in chords or intervals that are acoustically dissonant. However, they do introduce a degree of tension that, like an acoustically dissonant interval in species counterpoint, requires a smooth introduction and a specific resolution.

When one of these scale degrees is present in a chord with the corresponding function, the dissonant scale degree has a strong tendency to resolve down by step over the next change in function. In strict composition, we will always follow these tendencies.

In strict keyboard style, these functional dissonances should be “prepared” (approached) by common tone or by step. Thus, though they are proper members of the chord, melodically they will look like one of the three dissonance types of species counterpoint: a passing tone or neighbor tone dissonance that is approached by step, or a suspension dissonance that is approached by a common tone. The suspension type is preferred.

Once a functional dissonance is introduced, it must be resolved down by step in the same voice when the function changes. The dissonance can also be transferred to another voice before resolution—for instance, if there are multiple chords in a row exhibiting the same function, a dissonance that appears in the alto can be transferred to the tenor in the following chord, and then resolve in the tenor when the function changes. (It is more typical, and smoother sounding, to transfer dissonances between inner voices or from an inner voice to an outer voice than from an outer voice to an inner voice. Once a dissonance appears in the melody or bass, where it is more noticeable, it tends to resolve in that voice.)

Functional dissonance resolutions often cause conflicts with other principles of voice leading. Except in special cases such as schemata (standard patterns that are common enough to sound appropriate, even if they follow different rules), the functional dissonance resolution takes precedence over other principles such as the law of the shortest way, contrary motion with the bass, and preferring common tones and steps to melodic leaps. A dissonance resolution is never an excuse for illegal parallels, and only rarely will lead to non-standard doublings.