Inquiry-Based Music Theory OER Text Book

Lesson 4a - Simple Meters

Class Discussion

This was an interesting class because it was the first class at which I was not present for a majority of the class period, so the teaching assistants ran the exercises and discussion. I asked the graduate teaching assistant to start by ensuring that the class understood all of the terminology and definitions from Overview 4a. The following is my summation of the teaching assistants’ notes and my addendums.

In looking through the class notes, it does not seem that the class correctly identified the common characteristic of all simple meters. When asked to identify what all simple meters had in common, they landed on, “the top number of the time signature is divisible by two.” Not only is this not true for all simple meters (e.g. 3/4) as shown in Examples 4a, it still would not differentiate this class of meters from compound meters. 6/8 and 12/8 are both compound time signatures that have a top number that is divisible by two.

The definition is “simple”! (Music professor humor…) Simple meters are any regular meters in which the beat is divided into exactly two equal parts.

Duple, Triple, and Quadruple

The class came up with the following collections of duple, triple, and quadruple meters:

- simple duple meter: 2

- ex: 2/4, 2/2, 2/8, 2/16

- simple triple meter: 3

- ex: 3/4, 3/2, 3/8, 3/16

- simple quadruple meter: 4

- ex: 4/4, 4/2, 4/8, 4/16

This is correct but it doesn’t provide a definition of what these numbers mean. These words are used to signify how many beats are in a measure.

Simple time signatures

The class succesfully described the function of the top and bottom numbers of the time signature. For simple meter time signatures:

- the top number represents how many beats are in the measure

- the bottom number denotes what rhythmic value represents the beat

- if a 4 is on the bottom, the beat is represented by a quarter note

- if an 8 is on the bottom, the beat is represented by an eighth note

To easily figure out the bottom number’s rhythmic value, I always tell students to imagine that the bottom note becomes the denominator (lower number) of a fraction under a numerator of 1. A bottom number of 4 becomes 1/4 – a quarter. A bottom number of 2 becomes 1/2 – a half.

Beat-counting system in simple meters

It seems that for every unique syllable, there is a beat-counting system for affixing syllables to beats, divisions, and subdivisions. Each of these have their strengths and weaknesses, but for this theory course, we will be using the following for simple meters:

beat numbersfor each beat (e.g. 1, 2, 3, etc.)&for the division (e.g. 1-& 2-& etc.)e(pronounced ‘ee’) and a (pronounced ‘ah’) for the first level subdivisions (e.g. 1-e-&-a 2-e-&-a)

While this system can blend together aurally if said quickly, its primary benefit is that it has a unique syllable for each level through the first subdivision, and this makes communicating easier with higher specificity. For example, it is easy to ask, “Is the G4 on the ‘e’ of beat four a non-chord tone?”, and this does not require further information.

Theoretically ideal beaming versus common practice

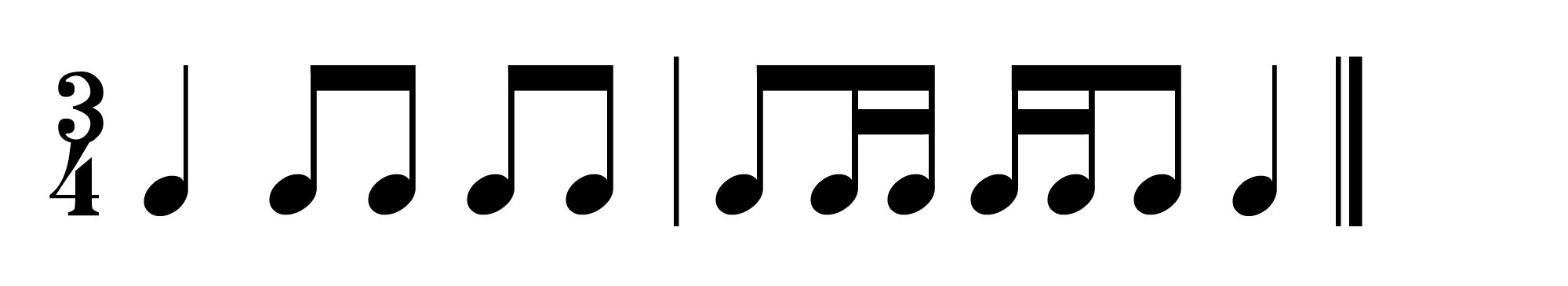

In Examples 4a, I asked the class to look at two examples of something I termed “theoretically ideal” beaming versus two counterparts of the same rhythm beamed in a more commonly used manner. The class came up with the following ideas:

- “Theoretically ideal” beaming shows where each beat occurs in an effort not to obscure the beat

- Half notes and whole notes are obvious exceptions.

- This focuses more on eighth notes, sixteenth notes, and further subdivisions.

This is very much inline with my general intention. Well-engraved music is meant to look pleasing and be easy for a performer to read. This often leads to grouping rhythmic patterns according to non-rhythmic ideas: lyrics, spacing measures across the page, phrasing, a limited number of systems, etc. Theoretically ideal beaming would never obscure a beat in order to provide the easiest reading of harmony within a score. Of course, no musician will ever use this in its stricest form because it would become difficult to read in many situations; imagine not using a whole note in 4/4 time and instead using four tied quarter notes.

That being said, it is important for students of music to begin trying to understand how grouping and beaming decisions are made, because in harmonic analysis, it is easy to sometimes miss voices because of obscured beats. It is also an excellent thought exercise to help students to begin demonstrating mastery of meters and rhythmic values.

Further Reading

From Open Music Theory

Meters

Meter involves the way multiple pulse layers work together to organize music in time. Standard meters in Western music can be classified into simple meters and compound meters, as well as duple, triple, and quadruple meters.

Duple, triple, and quadruple classifications result from the relationship between the counting pulse and the pulses that are slower than the counting pulse. In other words, it is a question of grouping: how many beats occur in each bar. If counting-pulse beats group into twos, we have duple meter; groups of three, triple meter; groups of four, quadruple meter. Conducting patterns are determined based on these classifications.

Simple and compound classifications result from the relationship between the counting pulse and the pulses that are faster than the counting pulse. In other words, it is a question of division: does each beat divide into two equal parts, or three equal parts. Meters that divide the beat into two equal parts are simple meters.

There are three types of standard simple meters in Western music:

- simple duple (beats group into two, divide into two)

- simple triple (beats group into three, divide into two)

- simple quadruple (beats group into four, divide into two)

In a time signature, the top number (and the top number only!) describes the type of meter. Following are the top numbers that always correspond to each type of meter:

- simple duple: 2

- simple triple: 3

- simple quadruple: 4

Notating meter

In simple meters, the bottom number of the time signature corresponds to the type of note corresponding to a single beat. If a simple meter is notated such that each quarter note corresponds to a beat, the bottom number of the time signature is 4. If a simple meter is notated such that each half note corresponds to a beat, the bottom number of the time signature is 2. If a simple meter is notated such that each eighth note corresponds to a beat, the bottom number of the time signature is 8. And so on.

Beaming

It’s important to remember that notation is intended to be read by performers. You should always strive to make your notation as easy to interpret as possible. Part of this includes grouping the rhythms such that they convey the beat unit and the beat division. Beams are used to group any notes at the beat division level or shorter that fall within the same beat.

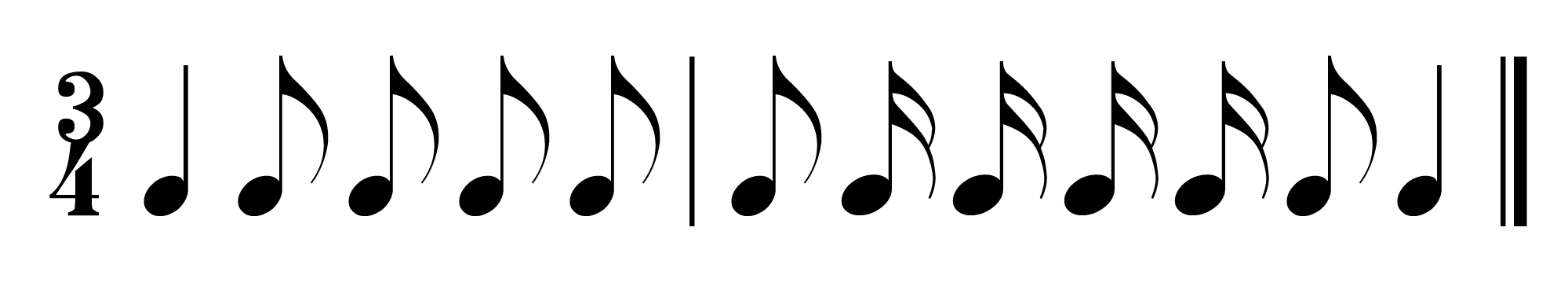

In this example, the eighth notes are not grouped with beams, making it difficult to interpret the triple meter.

If we re-notate the above example so that the notes that fall within the same beat are grouped together with a beam, it makes the music much easier to read.

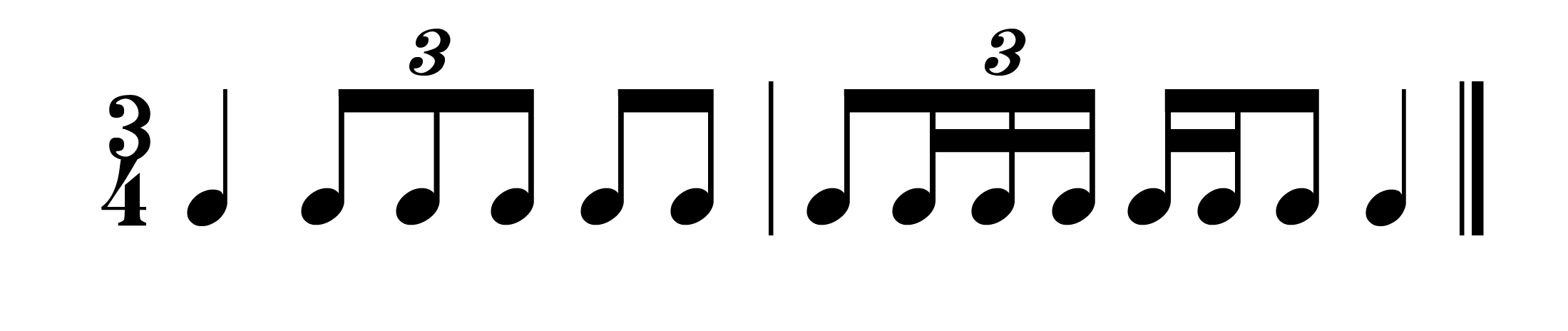

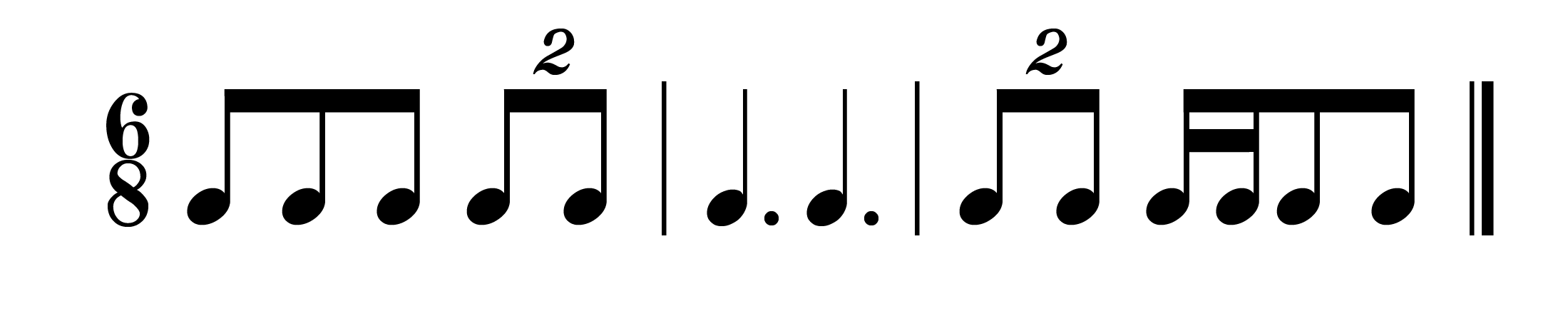

Borrowed divisions

Typically, a meter is defined by the presence of a consistent beat division: division by two in simple meter, and by three in compound meter. Occasionally, composers will use a triple division of the beat in a simple meter, or a duple division of the beat in a compound meter.

Triplets are borrowed from compound meter, and may occur at both the beat division and subdivision levels, as seen below.

Likewise, duplets can be imported from simple meter into a compound meter.

Hearing meter

For a more detailed explanation of meter with an emphasis on hearing and recognizing standard meters, see the following two videos:

Meter - counting pulse from Kris Shaffer on Vimeo.

Meter - grouping and division from Kris Shaffer on Vimeo.

Following are the musical examples referenced in the above videos:

"Come Out Clean," Jump Little Children

"With or Without You," U2

"The Tourist," Radiohead

Examples

Simple duple meter

Symphony No. 5, Movement IV., Ludwig van Beethoven

"Idioteque," Radiohead

Sonata No. 1 in F Minor, Op. 2, No. 1, Movement I., Ludwig van Beethoven

Simple triple meter

String Quartet No. 15 in D Minor, K. 421, Movement III., Wolfgang A. Mozart

Symphony No. 90 in C Major, Hob: I:90, Movement III., Joseph Haydn

Simple quadruple meter

"With or Without You," U2

"Come Out Clean," Jump Little Children

"Shh," Imogen Heap