Inquiry-Based Music Theory OER Text Book

Lesson 1b - Labeling Pitches

Class Discussion

Enharmonic Equivalence and Pitch-Classes

Using the example material to look at examples of enharmonic equivalents, the class worked together to determine which pitch-classes had three enharmonic equivalents and which had two. The first two examplex given were:

A, B-double-flat, G-double-sharp B, C-flat, D-double-sharp

Each note in these groups belong to the same pitch-class, because they share an identical frequency in their sound waves. Yet they function differently within the context of music, so we have multiple ways of labeling the same frequency.

The most important realization was that letter system employed in staff notation is the limiting factor in creating enharmonic equivalents within a pitch-class. The pitch-class that includes A-flat is isolated from its neighbors in such a way that there is no pitch that uses the letter F or B to create a third enharmonic equivalent if we limit ourselves to only the five common accidentals. The interaction between the 7 letter names and 12 pitch-classes is the basis for our musical notation system and will be critical in how we label intervals, chords, and scales.

Labeling Octaves

Using the examples, the class was able to determine a few simple rules to label octaves using ISO system.

- Notes are labeled using a pitch name and a number.

- The numbers represent an octave range and higher numbers equate to higher octaves.

- Each number starts on C.

- Each number ends on B.

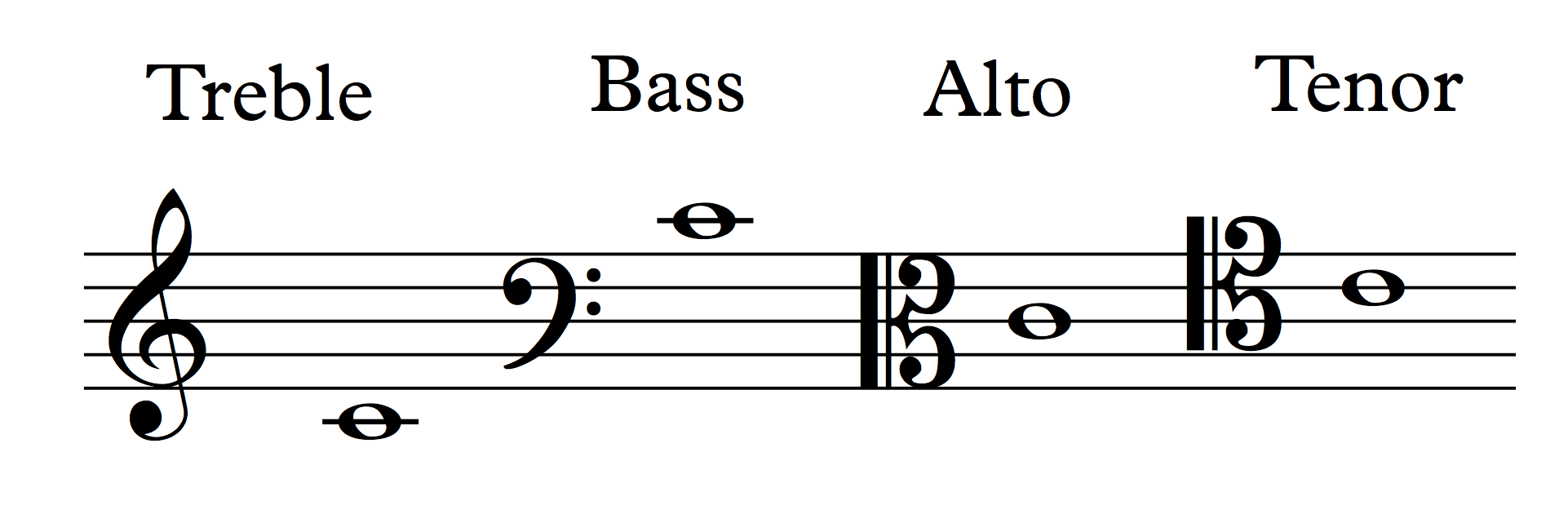

From the topic overview, they knew that C4 is middle C, and from this, they were able to determine where middle C is on each clef

From this, it is easy to see the necessity of clefs. Ledger lines are an important notational tool, but too many ledger lines becomes difficult to read quickly. Therefore, each clef highlights a specific range that can be written without employing ledger lines. Alto clef is typically employed as a lower treble clef, while tenor clef is a higher bass clef. Of course, alto and tenor clef have similar ranges and one of the other could likely be eliminated with little issue, but because both of these clefs have been widely used for more than a century, it is necessary for all musicians to at least be familiar with reading them.

Notes from Dr. Butterfield

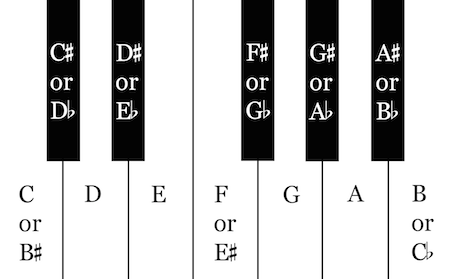

At the end our discussion, we began an interresting conversation on why the ISO system is based of C rather than A. Of course, this is almost entirely related to the evolution of the musical notation system and how the non-accidental pitches (i.e. “white keys” of the keyboard) form a major scale. We began a brief discussion of the physics of sound, and how pitch is a mental construct of the human mind in order to internalize and make sense of the mathematics of the vibrations that enter our ear. While this is a fascinating topic, it is somewhat beyond the purview of this chapter, but I hope to finish this discussion in a later class.

Further Reading

From Open Music Theory

The Keyboard

The keyboard is great for helping you develop a visual, aural, and tactile understanding of music theory. On the illustration below, the pitch-class letter names are written on the keyboard.

Enharmonic equivalence

Notice that some of the keys have two names. When two pitch classes share a key on the keyboard, they are said to have enharmonic equivalence. Theoretically, each key could have several names (the note C could also be considered D♭♭, for instance), but it’s usually not necessary to know more than two enharmonic spellings.

Octave Designation

When specifying a particular pitch precisely, we also need to know the register. In fact, if all you have is C-sharp or B-flat, you do not have a pitch, you have a pitch-class. A pitch-class plus a register together designate a specific pitch.

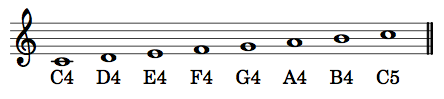

We will follow the International Standards Organization (ISO) system for register designations. In that system, middle C (the first ledger line above the bass staff or the first ledger line below the treble staff) is C4. An octave higher than middle C is C5, and an octave lower than middle C is C3.

Here is the pitch C4 placed on the treble, bass, alto, and tenor clefs.

The tricky bit about this system is that the octave starts on C and ends on B. So an ascending scale from middle C contains the following pitch designations:

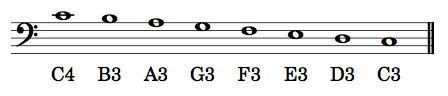

And a descending scale from middle C contains the following pitch designations:

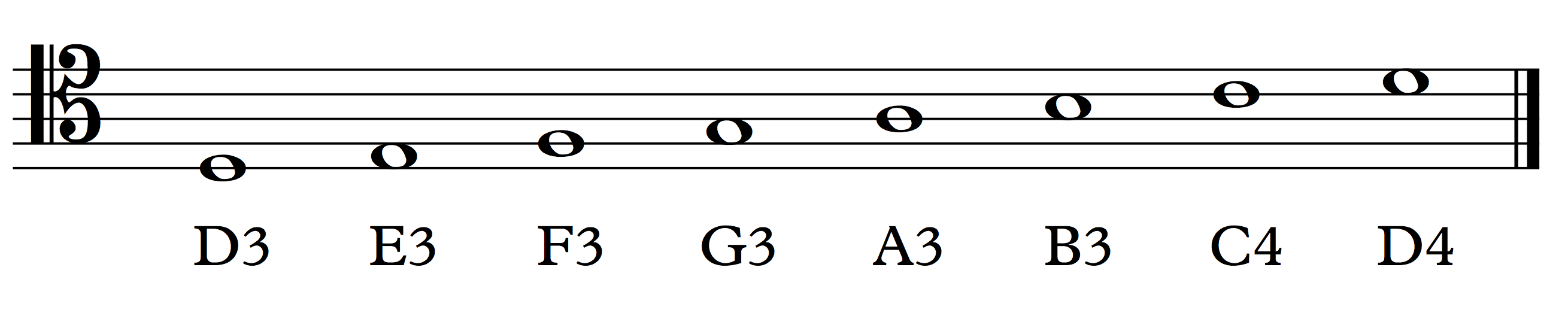

Pitches on the alto staff are as follows:

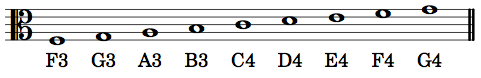

Pitches on the tenor staff are as follows:

Any accidentals follow the octave designation of the natural pitch with the same generic name. Thus a half step below C4 is C-flat4 (even though it sounds the same as B3), and a half step above C4 is C-sharp4.

Note that a complete designation contains both the pitch-class name (a letter name plus an optional sharp or flat) and the register (the ISO number indicating the octave in which the pitch is found). Unless both are present, you do not have the full designation of a specific pitch.