Inquiry-Based Music Theory OER Text Book

Lesson 2a - Identifying and Labeling Intervals

Class Discussion

Now that we have formalized our notation of the most basic level of music notation – a single pitch – we must find a method to measure the distance between two pitches. Any two-note combination is called a dyad, and the distance between the two pitches of a dyad is called an interval.

Our goal when measuring intervals is intrinsically tied to the tonal system that we use, diatonic harmony. The simplest way to measure the distance between two intervals would be to measure the distance by the least common multiple of our octave – in this case, a half-step (minor second). While easily understandable, this method does not relate to our concept of tonality. Instead, counting half-steps creates interval-classes in which intervals are considered equal regardless of the pitches. For example, the interval of G to D-flat has six half-steps which is identical to the interval from C-sharp to G. Both even use the same pitch-classes, however, any person familiar with diatonic harmony will immediately associate these two intervals with different key centers. (G to D-flat is strongly associated with the key of A-flat major/minor, whereas C-sharp to G likely implies D major/minor.) The context of these two intervals is critical in determining their function in tonal harmony, so we must use a system that differentiates between the two.

In a diatonic labeling system, every interval has a size and a quality.

For example, in a minor second, labeled m2, the m indicates the quality or the interval and the 2 indicates the size of the interval.

Interval size

After much discussion, the class determined that size can be determined by considering either:

- lines and spaces

- letter names

Both these ideas get the same result, although counting letter names can yield results without requiring the presence (or imagination) of a staff. Do not forget that you must include the bottom letter when counting.

This means that any interval that has two letters in the same order will always have the same size regardless of key signatures and/or accidentals. Using our previous example, the size of the interval between G and D-flat is a fifth. We can change the bottom note to any other G (G-sharp, G-flat, etc.) and the top note to any other D (D-sharp, D-natural, etc.), but the size of that interval will always be a fifth. Yet if we exchange the D-flat for its enharmonic equivalent, C-sharp, we alter the letters and turn the size of the interval into a fourth.

Interval quality

(If you are completely unfamiliar with scales, you may want to skip one topic ahead to scales (2b), and then return to this after beginning to understand the construction of the major scale. For a method that does not rely on knowledge of major scales, you can also scroll to the bottom of this section and read a useful method from the writers of Open Music Theory.)

Interval quality is difficult to examine without beginning to think about our concept of tonality and keys. One student succinctly explained her straightforward method for finding the quality, and it revolved around a strong familiarity of the twelve major scales:

- Please remember that each of the following steps only works if you consider

doas the bottom pitch of the interval. - When looking at an interval, consider the bottom pitch of the interval as

doof a major scale. - If the top pitch of the interval is a note that already exists in that major scale, it is either a major or perfect interval. Whether major or perfect depends on the size.

- Unisons, fourths, fifths, and octaves occur naturally as perfect intervals within the major scale.

- Seconds, thirds, sixths, and sevenths occur naturally as major intervals within the major scale.

- Any alteration from the basic major and perfect intervals can then be labeled by looking at the direction of alteration and the number of half-steps that the interval was altered.

- If the original interval is perfect:

- Raising the interval by a half-step creates an augmented interval.

- Lowering the interval by a half-step creates a diminished interval.

- If the original interval is major:

- Raising the interval by a half-step creates an augmented interval.

- Lowering the interval by a half-step creates a minor interval.

- Lowering the interval by a 2 half-steps creates a diminished interval.

- If the original interval is perfect:

From this, our interval hierarchies were grouped as:

- Interval sizes of 1, 4, 5, and 8 can only have the qualities of perfect, augmented, or diminished.

- Interval sizes of 2, 3, 6, and 7 can only have the qualities of major, minor, augmented, or diminished.

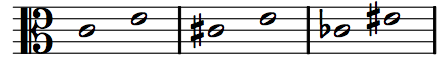

Some examples using this method:

CtoE:- Counting the letter names confirmed that the size is a third (C, D, E = 3)

- By using the lower pitch,

C, asdo, we know that the naturally occurringEin the key of C major isE-natural. - Because this is a third, we know that the naturally occurring note must use the major hierarchy, so therefore,

E-naturalwould be a major third *(M3) above C.

DtoG-sharp- Counting the letter names confirmed that the size is a fourth (D, E, F, G = 4)

- By using the lower pitch,

D, asdo, we know that the naturally occurringGin the key of D major isG-natural. - Because this is a fourth, we know that the naturally occurring note must use the perfect hierarchy, so therefore,

G-naturalwould be a P4 above D. - Because

G-sharpis one half-step above the perfect interval, we know that this interval is an augmented fourth (A4).

FtoE-double-flat- Counting the letter names confirmed that the size is a seventh (F, G, A, B C, D, E = 7)

- By using the lower pitch,

F, asdo, we know that the naturally occurringEin the key of F major isE-natural. - Because this is a seventh, we know that the naturally occurring note must use the major hierarchy, so therefore,

E-naturalwould be a M7 above F. - Because

E-double-flatis two half-steps below the major interval, we know that this interval is an diminished seventh (d7).

Note that even though perfect intervals use a different hierarchy than major/minor intervals, but both hierarchies share the terms diminished and augmented.

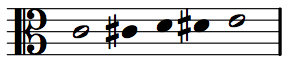

Melodic vs. Harmonic

Melodic and harmonic intervals were the easiest differentation for the students, although the use of terminology was mildly problematic. The first student described harmonic intervals as occurring “at the same time” while melodic intervals occur “at different times”. All students agreed that this was the simplest explanation, but we must be careful in how we apply the terms interval and pitches. The interval is the space between the two pitches, therefore, the interval cannot occur “at the same time” or “at different times”. The pitches can occur simultaneously or consecutively, but the interval always exists as a fixed measurement. This is how we can label harmonic and melodic intervals using the same system.

I recommended that we think of intervals as existing on either a horizontal or vertical axis, because we can visualize axes (as in the plural of axis) easily on musical staff notation. If two pitches occur “at the same time”, they will be aligned vertically on a staff. If two pitches occur consecutively, they will represent unique points on a horizontal line that runs parallel to the lines of the staff. This may seem overly technical, but it is an important distinction.

The final note was that melodic intervals can have two modifiers attached to them: ascending or descending. Ascending intervals start with the lower of the two pitches, whereas descending intervals start on the the higher pitch. Harmonic intervals cannot be ascending or descending.

Simple vs. Compound

The students immediatly discerned that simple intervals include any interval that is equal to or smaller than an octave. Compound intervals are any interval larger than an octave.

To label compound intervals, we count letter names as we do for simple intervals. We can find a compound interval by adding 7 to any simple interval. For example, a 2nd becomes a 9th. A 4th becomes an 11th. An 8ve (octave) becomes a 15th.

Conversely, if we see a compound interval, we can find its simple equivalent by subtracting 7. A 12th is a 5th plus an 8ve. A 10th is a 3rd plus an 8ve.

One student asked why we don’t add eight considering that we are adding an octave. The problem lies in how we find the size of intervals. When we find interval size, we count the letter names and include the starting note. When we add an octave, we have already used the top note so we are missing one letter. For example, a fifth from A to E includes the letters A B C D E. If we add an octave, the first E was already included in the first interval of the 5th, so we are only adding seven letters F G A B C D E.

Chromatic vs. Diatonic

The difference between chromatic and diatonic was the most straightforward of the classifications for the class to explain. Simply put, diatonic intervals use only the notes of the given key signature, while chromatic intervals have accidentals to alter one of both of the pitches.

Inversions

The class figured out both of their guidelines for inversions quickly. For this discussion, we are considering an inversion to be an interval in which one pitch is fixed and the other is displaced by an octave toward the fixed pitch.

To determine the size of an inverted interval, the first student pointed out that you could create a grid of size pairs, so:

- 4 inverts to 5

- 3 inverts to 6

- 2 inverts to 7

- 1 inverts to 8

A second student pointed out that each of these pairs add up to nine, so if you would like to not memorize this grid, you can find an inversion by simply subtracting the size from 9. For example, if there is a written 3rd, subtract 3 from 9 to find that the inversion of a 3rd is a 6th. Note that for compound intervals, you must use subtract from 16 or use negative numbers and absolute values. Because of this, it is easier to reduce compound intervals to a simple interval before inverting.

To find the qualities of inverted intervals, the students agreed that memorizing three pairs is the easiest method:

- diminished becomes augmented

- major becomes minor

- perfect becomes perfect

Further Reading

From Open Music Theory

Defining an Interval

An interval is the distance between two pitches, usually measured as a number of steps on a scale.

A dyad is a pair of pitches sounding together (in other words, a two-note chord). Since a dyad is defined by the interval between the two pitches, dyads are often simply called intervals.

Thus, the term interval regularly refers both to the distance between two pitches on a scale and to a dyad whose pitches are separated by that distance.

Diatonic intervals

More commonly for tonal music, we are interested in the number of steps on the diatonic (major or minor) scale. This is a bit tricky—not because it’s difficult, but because it’s counter-intuitive. Unfortunately, the system is too old and well engrained to change it now! But once you get past the initial strangeness, diatonic intervals are manageable.

When identifying a diatonic interval, begin with the letter names only. That is, treat C, C-sharp, and C-flat all as C for the time being. Next, count the number of steps (different letters) between the two pitches in question, including both pitches in your count. This gives you the generic interval.

For example, from C4 to E4, counting both C and E, there are three diatonic steps (three letter names): C, D, E. Thus, the generic interval for C4–E4 is a third. The same is true for any C to any E: C#4 to E4, Cb4 to E#4, etc. They are all diatonic thirds.

Often more specificity is needed than generic intervals can provide. That specificity comes in the form of an interval’s quality. Combining quality with a generic interval name produces a specific interval.

There are five possible interval qualities:

- augmented (A)

- major (M)

- perfect (P)

- minor (m)

- diminished (d)

To obtain an interval’s quality, find both the generic interval and the chromatic interval. Then consult the following table to find the specific interval.

| unis. | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th | 6th | 7th | oct. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| i0 | P1 | d2 | ||||||

| i1 | A1 | m2 | ||||||

| i2 | M2 | d3 | ||||||

| i3 | A2 | m3 | ||||||

| i4 | M3 | d4 | ||||||

| i5 | A3 | P4 | ||||||

| i6 | A4 | d5 | ||||||

| i7 | P5 | d6 | ||||||

| i8 | A5 | m6 | ||||||

| i9 | M6 | d7 | ||||||

| i10 | A6 | m7 | ||||||

| i11 | M7 | d8 | ||||||

| i12 | A7 | P8 |

For example, C4–E4 is a generic third, and has a chromatic interval of i4. A third that encompasses four semitones is a major third (M3). Note that both generic interval and chromatic interval are necessary to find the specific interval, since there are multiple specific diatonic intervals for each generic interval and for each chromatic interval.

Note that some generic intervals can be augmented, perfect, or diminished, and other intervals can be augmented, major, minor, or diminished. There is no generic interval that can be both major/minor and perfect; if it can be major or minor, it cannot be perfect, and if it can be perfect, it cannot be major or minor. An augmented version of an interval is always one semitone wider than major or perfect; diminished is always one semitone smaller than minor or perfect.

Solfège can also help to determine the specific interval. Each pair of solfège syllables will have the same interval, no matter what the key, as long as it is clear which syllable is the lower pitch and which is the upper pitch. Memorizing the intervals between solfège pairs can help speed along your analysis of dyads as they appear in music. For example, knowing that do–mi, fa–la, and sol–ti are always major thirds and knowing that re–fa, mi–sol, la–do, and ti–re are always minor thirds will allow for faster analysis of dyads in major keys.

Chromatic intervals

The simplest way to measure intervals, particularly at the keyboard, is to count the number of half-steps, or semitones, between two pitches. To determine the chromatic interval between C4 and E4, for example, start at C4 and ascend the chromatic scale to E4, counting steps along the way: C#4, D4, D#4, E4. E4 is four semitones higher than C4. Chromatic intervals are notated with a lower-case i followed by an Arabic numeral for the number of semitones. C4–E4 is four semitones, or i4.

Compound intervals

The intervals discussed above, from unison to octave, are called simple intervals. Any interval larger than an octave is considered a compound interval. Take the interval C4 to E5. The generic interval is a tenth. However, it functions the same as C4 to E4 in almost all musical circumstances. Thus, the tenth C4–E5 is also called a compound third. A compound interval takes the same quality as the corresponding simple interval. If C4–E4 is a major third, then C4–E5 is a major tenth.

Interval inversion

In addition to C4–E4 and C4–E5, E4–C5 also shares a similar sound and musical function. In fact, any dyad that keeps the same two pitch classes but changes register will have a similar sound and function. However, the fact that E4–C5 has E as its lowest pitch instead of C means that it has a different generic interval: E4–C5 is a sixth, not a third. Because of that difference, it will also play a different musical function in some circumstances. However, there is no escaping the relationship.

Dyads formed by the same two pitch classes, but with different pitch classes on bottom and on top, are said to be inversions of each other, because the pitch classes are inverted. Likewise, the intervals marked off by those inverted dyads are said to be inversions of each other.

Again, take C4–E4 (major third) and E4–C5 (minor sixth). These two dyads have the same two pitch classes, but one has C on bottom and E on top, while the other has E on bottom and C on top. Thus, they are inversions of each other.

Three relationships exhibited by these two dyads hold for all interval inversions.

First, the chromatic intervals add up to 12. (C4–E4 = i4; E4–C5 = i8; i4 + i8 = i12) This is because the two intervals add up to an octave (with an overlap on E4).

Second, the two generic interval values add up to nine (a third plus a sixth, or 3 + 6). This is because the two intervals add up to an octave (8), and one of the notes is counted twice when you add them together. (Remember the counterintuitive way of counting off diatonic intervals, where the number includes the starting and ending pitches, and when combining inverted intervals, there is always one note that gets counted twice—in this case, E4.)

Lastly, the major interval inverts into a minor, and vice versa. This always holds for interval inversion. Likewise, an augmented interval’s inversion is always diminished, and vice versa. A perfect interval’s inversion is always perfect.

major ↔ minor

augmented ↔ diminished

perfect ↔ perfect

Interval inversion may seem confusing and esoteric now, but it will be an incredibly important concept for the study of voice-leading and the study of harmony.

Methods for learning intervals

Ultimately, intervals need to be committed to memory, both aurally and visually. There are, however, a few tricks to learning this quickly. One such trick is the so-called white-key method.

White-Key Method

The white-key method requires you to memorize all of the intervals found between the white keys on the piano (or simply all of the intervals in the key of C major). Once you’ve learned these, any interval can be calculated as an alteration of a white-key interval. For example, we can figure out the interval D4-F#4 if we know that the interval D4-F4 is a minor third, and this interval has been made one semitone larger: a major third.

Conveniently, there is a lot of repetition of interval size and quality among white-key intervals. Memorize the most frequent type, and the exceptions.

All of the seconds are major except for two: E-F, and B-C, which are minor.

All of the thirds are minor except for three: C-E, F-A, and G-B, which are major.

All of the fourths are perfect except for one: F-B, which is augmented.

Believe it or not, you now know all of the white-key intervals, as long as you understand the concept of interval inversion. For example, if you know that all seconds are major except for E-F and B-C (which are minor), then you know that all sevenths are minor except for F-E and C-B (which are major).

Once you’ve mastered the white-key intervals, you can figure out any other interval by adjusting the size accordingly.

Melodic and harmonic intervals

The last distinction between interval types to note is melodic v. harmonic intervals. This distinction is simple. If the two pitches of a dyad sound at the same time (a two-note chord), the interval between them is a harmonic interval. If the two pitches in question are sounded back-to-back (as in a melody), the interval between them is a melodic interval. This distinction is important in voice-leading, where different intervals are preferred or forbidden in harmonic contexts than in melodic contexts. The difference is also important for listening, as hearing melodic and harmonic intervals of the same quality requires different techniques.

Consonance and dissonance

Intervals are categorized as consonant or dissonant based on their sound (how stable, sweet, or harsh they sound), how easy they are to sing, and how they best function in a passage (beginning, middle, end; between certain other intervals; etc.). Different standards apply to melody and harmony. The following categories will be essential for your work in strict voice-leading, and they will be a helpful guide for free composition and arranging work, as well.

Melodic consonance and dissonance

The following melodic intervals are consonant, and can be used in strict voice-leading both for successive pitches and as boundaries of stepwise progressions in a single direction:

- All perfect intervals (P4, P5, P8)

- All diatonic steps (M2, m2)

- Major and minor thirds

- Major and minor sixths

All other melodic intervals are dissonant, and must be avoided for successive pitches and as boundaries of stepwise progressions in a single direction, including:

- All augmented and diminished intervals (including those that are enharmonically equivalent to consonant intervals, such as A2 and A1)

- All sevenths

Harmonic consonance and dissonance

The following harmonic intervals are imperfect consonances, and can be used relatively freely in strict voice-leading (except for beginnings and endings):

- Major and minor thirds

- Major and minor sixths

The following harmonic intervals are perfect consonances, and must be used with care in limited circumstances in strict voice-leading:

- All perfect intervals except the perfect fourth (P1, P5, P8)

All other harmonic intervals are dissonant, and must be employed in very specific ways in strict voice-leading, including:

- All diatonic steps (M2, m2)

- All augmented and diminished intervals (including those that are enharmonically equivalent to consonant intervals, such as A2 and A1)

- All sevenths

- Perfect fourths