Inquiry-Based Music Theory OER Text Book

Lesson 4c - Metric perception

Class discussion

Syncopation

Syncopation occurs when emphasis is put on the weak beats of the meter, but the first example shows the subjectivity of this. When the class listened to the bottom line of the first example without the top line, every person heard it as starting on the beat. This may be obvious, but it is worth stating that strong and weak beats are determined by context, not by meter. Once the top line is added to the excerpt, the bottom line becomes a strongly syncopated rhythm. Syncopation can occur within a single line if the beat is established first and then off-beat rhythms are introduced, but this is still an example of establishing the strong beats for the listener before syncopation can begin.

Written time signatures versus aural perception

The second excerpt demonstrated how a variation – in this example, melodic shape – can affect listener perception. Aurally, both parts sounded identical regardless of the meter, but when listening and not looking at the excerpt, most students felt that the piece was in a compound duple meter. This demonstrates that even though a pattern can be written in various meters, there are other factors that can strongly pull toward a particular meter. In this case, the motif is melodically grouped into two groups of three, so it pull most of the listeners toward a 6/8 feel. The one student that heard it in 3/4, heard it as heavily syncopated.

The class noted that other factors such as accents, silence, and tempo can all have a strong effect on how a listener perceives a particular passage.

It should be noted that many composers rely on using meters to evoke particular rhythmic biases in the performer, so it is disingenuous to say that meter is entirely subjective. Stravinsky was well-known to write the same passage in various meters (e.g. Rite of Spring, L’histoire du Soldat), so a good performer is aware of what the meter is trying to tell them.

Previous material affecting perception

By starting at this particular point in the piece, most listeners will hear this section in a slow, simple triple meter. But an observant student may have noticed the conductor in the background (around the 2:29 mark) conducting in a double-time three, which means that the conductor is placing an off-beat where the listener is likely hearing beat 2 of their slow simple triple meter. If we move our starting point backward by only ten seconds, we hear the original groove of this section of the tune, which is the origin of the double-time simple triple meter that we saw the conductor using.

By starting at this new point, many listeners will switch to a faster (double-time) simple triple meter. The listener may or may not carry this feel through the half-time section from the first clip, but given the conductor’s beat pattern, we can be fairly certain that the orchestra is counting this section as if there is no change in meter.

Perhaps even more interesting is the effect on the listener when we move our starting point back into the the intro of the piece.

The introduction is clearly in a slow compound quadruple meter. The melody happens mostly at the beat level, and the cellos have a constant arpeggio at the subdivision level. At the 1:20 mark, there is a slightly disconcerting two-beat transition, and then a new section starts that most listeners will hear as a continuation of the slow compound quadruple meter of the intro. This is reinforced by an ostinato in a contra-bass clarinet as well as the body language of the performers. When the trumpet and saxophone enter with a new melody at 1:32, we realize that this slow compound quadruple meter is the exact same feel and melody that we heard as a fast simple triple melody in the second clip.

The conclusion of this exercise should be that the listener’s perception of meter is not tied to what is on the page, only to a complex array of aural input. Therefore, we can discuss meter in an objective manner by looking at what is written, but a listener is not required to hear the meter similarly to an analysis or even in the way in which the composer intended.

Further Reading

From Open Music Theory

Syncopation

Syncopation occurs when a rhythmic pattern that typically occurs on strong beats or strong parts of the beat occurs instead on weak beats or weak parts of the beat. Most pop/rock songs have a mixture of syncopated and “straight” rhythms. The syncopated rhythms are usually easy to sing, since they often match speech better than straight rhythms. However, they are more difficult than straight rhythms to sight-sing, dictate, or transcribe.

Straight syncopations

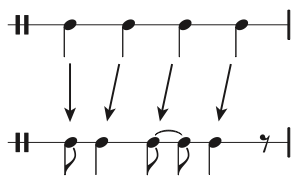

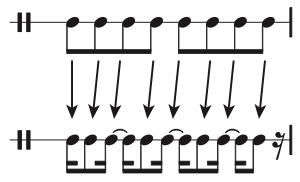

In contemporary pop/rock music, syncopation typically involves taking a series of notes of equal durations, cutting the duration of the first note in half, and shifting the rest early by that half duration.

For example, a series of four quarter notes, all sounding on the beat, can be transformed in this way by making the first note into an eighth note, and sounding each successive quarter note on eighth note early—all on the offbeats.

This process can occur on any metrical level. If the duration of the series of “straight” notes is two beats, they will be syncopated by changing the first note to a single beat and shifting each other note early by a beat. If the duration of the straight notes, like the figure above, is a beat, they will be syncopated by a division (one half beat in simple meter). If the straight notes are each divisions, they will be syncopated by shifting each note by a subdivision. The unit of syncopation (the duration of the first note, and the amount of shift applied to the following notes) is always half of the duration of the straight notes. All of these syncopations are realtively common in contemporary pop/rock music.

As a convention, when we take a series of notes that each have a duration of one beat and shift them early by half of a beat, we will call that beat-level syncopation. When we take a series of notes that each have a duration of one division and shift them early by a subdivision, we will call that division-level syncopation.

(Note the use of ties to make each beat clear. Always do this in order to make it easy to read.)

Transcribing straight syncopations

Straight syncopated rhythms are easily identified by the frequently occuring off-beat rhythms. For example, if you conduct or tap the counting pulse while listening to a song, several notes in a row that are articulated between your taps or conducted beats, with no notes articulated simultaneously with the counting pulse, indicate syncopation.

Once you identify a syncopated passage—which may only involve two or three notes—figure out on what metrical level the syncopation occurs. For example, in simple meter, if no notes are articulated directly on the counting pulse beats and one note is articulated in between each beat, the syncopation is occuring at the beat level. If no notes are articulated directly on the counting pulse beats and two notes are articulated in between each beat, listen to the passage again while tapping the division. If no notes are articulated directly on the division taps and one note is articulated in between each tap, the syncopation is occuring at the division level.

Once you have determined the metrical level on which the syncopation occurs, determine the durational value of the shift. If the syncopation occurs on the beat level (one note sounding between each counting pulse beat), the value of syncopation is a division: each beat-length note has been shifted one division early. If the syncopation occurs on the division level, the value of syncopation is a subdivision: each division-length note has been shifted one subdivision early.

Lastly, determine how the syncopated pattern begins. Does the offbeat pattern simply begin offbeat? Or does the pattern begin with two quick notes back-to-back as above—one short note on the beat followed by the first of the longer syncopated notes?

Once you have determinted the level of syncopation, the duration of the shift, and whether or not the pattern begins with a truncated onbeat note, the rhythmic pattern should be easy to notate. If, however, you are still having difficulty, try using the lyric syllables and the stress patterns of the lyrics to help you keep track of the individual notes and which ones are on/offbeat. Writing lyrics down before notating the rhythm can be a big help.

Fake triplets

Another common rhythmic pattern in pop/rock is to divide a beat (or two beats) into three almost-equal groups. For example, dividing a half note into two dotted-eighth notes and an eighth note (3+3+2). Since this pattern approximates a triplet while still maintaining the simple division of beats by 2, 4, 8, etc., we can call them fake triplets.

Fake triplets are more common than “real” triplets in most pop/rock genres, but both do occur, so take care to distinguish between the two. “Cathedrals” by Jump, Little Children contains examples of both (as well as some straight syncopation), and is an excellent example for practicing performing and identifying fake and real triplets.

While fake triplets occur most often in 3+3+2 groupings, 3+2+3 and 2+3+3 are also possible.

A related pattern is what we might call fake sextuplets. Here the 3+3+2 pattern is doubled, resulting in 3+3+3+3+2+2.

In the opening of “Electric Co.” by U2, the guitar plays subdivisions (sixteenths) grouped 3+3+3+3+2+2, while the kick drum plays straight beats (quarters) under the hi-hat playing straight subdivisions.

Demo

The following video walks through the process of transcribing straight syncopations in the song “Shh” by Frou Frou.