Inquiry-Based Music Theory OER Text Book

Lesson 7b - Performing a Harmonic Analysis

Class Discussion

Students often confuse harmonic analysis with identifying each of the harmonies. While finding chords is a part of harmonic analysis, the actual goal of harmonic analysis is to explain how the listener hears the music. To do this, we must figure out which pitches are functional and which pitches are embellishments. The essential pitches of any harmony are those that if removed, would noticeably alter the way the listener hears the harmony.

To move toward this goal, music theorists use a number of tools, most of which are designed to look at contextual clues and draw conclusions based on their general knowledge. We created one of these tools in Unit 7a with the diatonic harmonic flowchart.

| (unnamed) | (unnamed) | pre-dominant | dominant | tonic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| iii | vi | ii | V | I |

| IV | viio |

By employing the progressions from this flowchart, a theorist can look at a given harmony and decide which pitches support a harmonic progression that is likely to be heard by a listener. For an example of how this would work, refer to the third example under Examples 7a.

With nothing more than this, the students attempted a basic harmonic analysis of The Old Hundredth, a classic hymn with a standard SATB harmonization. I asked them to provide not only provide the chords in both leadsheet notation and Roman numerals, but also to take notes on questions that arose as they workeed through this process. They came up with three primary questions:

- How often does the harmony change?

- Which pitches are chord tones and non-chord tones?

- Which pitches are omitted from the harmony?

Harmonic rhythm

The first question was obvious to most, but difficult to tackle. How often does the harmony change? The rate at which harmonies change is called harmonic rhythm. This is often a chicken-or-the-egg question: you need to know how often the chord changes to determine which pitches to include in the chord, but you also need to look at which pitches create chords to figure out how often the chord changes. Chorales are an easy place to start, because most often, they change chords every quarter note; this creates an easy-to-see visual cue as each chord is stacked vertically and mostly homorhythmic. For more complicated textures, studying melodic patterns and bass-lines is often enough to provide enough context for an educated guess. Bass-lines in particular will often sustain pitches and/or outline chords until the harmony changes, and this gives a clear indicator of probable harmonic rhythm. This becomes much easier as the student gains experience.

Chord tones versus non-chord tones (NCTs)

Tackling the question of which pitches are functional means determining which pitches belong to the chord (chord tones) and which pitches are decoration for these chord tones. To this point, we have only looked at passing tones, neighbor tones, and suspensions. All of these require stepwise movement only, so any skip in our beginning examples will be a chordal skip. We will expand this as we begin looking at all of the classes of NCTs.

Much like determining the harmonic rhythm, finding NCTs can be difficult because it requires working through all possible combinations of the pitches within a given harmony and then choosing the most likely combination. Even if you know that the harmony includes only two beats, if there are many pitches within those two beats, it can be difficult to sort through all the possible combinations. Fortunately, the same strategies that work for looking at harmonic rhythm work for determining NCTs. Looking at melodic patterns and bass-lines is a great start, but it is also helpful to be aware of whether a note occurs in a strong or weak position. It is unusual for the functional tones to occur only on offbeats, as the ear is drawn to pitches when the occur on the beat.

Even for one experienced in finding patterns within the music, this still sometimes requires trial-and-error. For beginning students, I suggested that they try copying the pitches to another staff (or lightly next to the chord if there is room,) and begin rearranging the pitches to see what triads and seventh chords are even possible. Usually this is enough to limit the possibilities to one or two chords. When it is not, they should refer to their harmonic flowchart to see if there is some context that could provide a probable chord.

Notating non-chord tones

To nontate non-chord tones, you should place parentheses around the note head of each non-chord tone. You must also label the NCT with its abbreviation. Currently, we only have three possible NCTs:

- pt (passing tone)

- nt (neighbor tone)

- sus (suspension)

The students had an excellent question regarding non-chord tones.

- If there is a V chord with a chordal seventh in a moving line, should that be considered a V7?

- The most common answer is yes, but make sure that it functions as a chordal seventh. If it resolves down by step to the third of the following chord, it is best to include this as a functional chordal 7th. If it resolves another way (e.g. up by step), it might be a melodic passing tone and is therefore not functional.

Regardless of whether you include the pitch as functional, the NCTs must always match the Roman numeral. In this scenario, if you choose to include the chordal seventh in your harmony, you only need to write the proper Roman numeral and inversion figure. If, however, you decide that the chordal seventh is just a passing tone, you must label it as a non-chord tone and write only V for the Roman numeral.

Omitted tones

This was a brief discussion. Refer to the voicing guidelines under Unit 6b for likely doublings and omissions in four-part writing.

Further Reading

The three common-practice harmonic functions

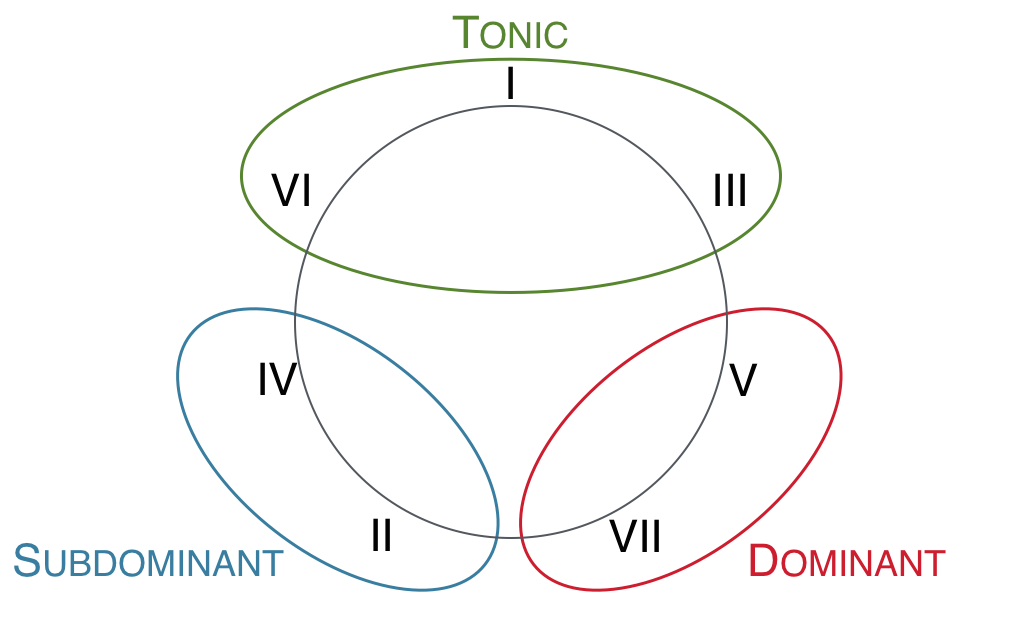

In common-practice music, harmonies tend to cluster around three high-level categories of harmonic function. These categories are traditionally called tonic (T), pre-dominant (P — sometimes referred to as subdominant, S), and dominant (D). Each of these functions has their own characteristic scale degrees, with their own characteristic tendencies. And each of these functions tend to participate in certain kinds of chord progressions more than others.

If you are already comfortable with Roman numerals, you can generally think of I, III, and VI as tonic, II and IV as pre-dominant, and V and VII as dominant. (Though, as you will see below, there is more to it than that.)

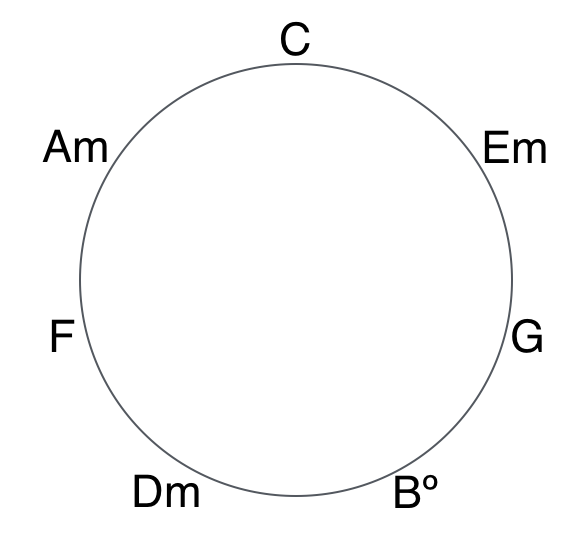

To visualize these functional categories, think of the usual triads in C major arranged on a circle of thirds. Note that each chord sits between the two triads that share the most tones in common — C major (C, E, G) sits between E minor (E, G, B) and A minor (A, C, E), both of which share two tones in common with C.

Convert these chords to Roman numerals (in C major), and we can see the functions. Since the function is determined by the tendencies of the tones that they share, and since on this graph chords are grouped together by notes they have in common, they are also grouped together by function.

Triads arranged on the circle of thirds, labeled by harmonic functions.

Interestingly, in common-practice music, a chord’s function can be determined solely by its internal characteristics (the notes that make up the chord). This is not true of all styles. For example, in pop/rock music a IV chord can exhibit very different functional tendencies depending on its context. But in classical music, simply knowing the notes in a chord is enough to determine its general harmonic function and the general tendencies of that chord and its individual notes.

The syntactic properties of these functions will be covered elsewhere. What follows simply explains how to determine the function of a chord in common-practice music with greater specificity.

Finding the function of a chord

Each of the three harmonic functions — tonic (T), pre-dominant (P), and dominant (D) — have characteristic scale degrees. Tonic’s characteristic scale degrees are 1, 3, 5, 6, and 7. Pre-dominant’s characteristic scale degrees are 1, 2, 3, 4, and 6. Dominant’s characteristic scale degrees are 2, 4, 5, 6, and 7.

Ian Quinn (a music theorist at Yale University) further distinguishes these scale degrees, using the categories of functional triggers, functional associates, and functional dissonances. These categories help us understand the functional properties of chords whose scale degrees belong to more than one function, as well as how certain notes behave within a chord. They also help us understand which scale degrees are more or less characteristic of a function ― something that will help determine function when a complete chord is not present.

| function | triggers | associates | dissonances |

|---|---|---|---|

| T | 1 and 3 | 5 and 6 | 5 (if 6 is also present) and 7 |

| P | 4 and 6 | 1 and 2 | 1 (if 2 is also present) and 3 |

| D | 5 and 7 | 2 | 4 and 6 |

In terms of moveable-do solfège:

| function | triggers | associates | dissonances |

|---|---|---|---|

| T | do and mi/me | sol and la/le | sol (if la/le is also present) and ti/te |

| P | fa and la/le | do and re | do (if re is also present) and mi/me |

| D | sol and ti/te | re | fa and la/le |

To determine the function of a chord, find the function that includes all the scale degrees of a chord (regardless of chromatic alterations ― that is, treat ♯4 the same as regular scale-degree 4). If more than one function contains all the scale degrees, take the function with the most triggers in the chord.

There is one exception to this (for now): a chord with scale degrees 6, 1, and 3 is a special kind of tonic chord, called a destabilized tonic. Quinn uses the special functional label is Tx, rather than simply T, for this chord.

Also note that because the III7 chord’s scale-degrees do not wholly belong to any of the three functions, it can behave similar to T and D chords, depending on context. It is a rare chord in its diatonic form.

This handout will help you determine the function of a chord from the bass scale degree and/or the Roman numeral.