Inquiry-Based Music Theory OER Text Book

Lesson 5a - Introduction to Counterpoint

Class discussion

The class discussion centered around the question, “Why study counterpoint in a tonal harmony class when there are entire courses in later semesters dedicated to this specific subject. After reading the assigned passage in the Overview, the class came up with the following suggestions:

- Music is structured to create expectations and then either fulfill or deny those expectations.

- Music is a built upon tension and release.

These are both true observations about the nature of musical composition in general, but they do not address the need to study counterpoint directly. So I asked the class, “What is counterpoint?” After an awkward silence, I directed them to the second sentence of the reading.

“Voice-leading deals with the relationship of two or more musical lines (or melodies) combined into a single musical idea.”

A brief study of counterpoint is the next step up for us as we work through the increasing levels of musical complexity. We began with a single pitch, then combined pitches to create intervals. We must then combine intervals to create melodies and combine melodies to create counterpoint. Studying counterpoint allows us to strip away many of the complicating factors of musical harmony and begin to understand the origin and basis for tonality.

In the next topic, we will establish some basic rules for constructing a simple melody and then look at what happens when we create a second melody that works with the original. It is from these interactions that harmony evolved as we know it, so to study counterpoint is to study the basis for music.

Eighteenth century species counterpoint gives us a relatively straightforward set of rules and norms to begin this study. Even though many of these rules are not observed by modern music, we can study the process of how these rules create music and then apply that process to all types of music.

This process is based on two primary functions: intervals and melodic motion.

Consonant vs dissonant intervals

From the examples, I asked the students to create lists of perfect consonances and imperfect consonances.

Consonant and Dissonant Intervals:

- Perfect Consonance:

- Perfect 5ths

- Perfect Octave

- Perfect Unison

- (The perfect 4th was mentioned, but it was not in the examples.)

- Imperfect Consonance:

- Major 3rd

- Minor 3rd

- Major 6th

- Minor 6th

- Dissonance:

- All other intervals, but the most common are:

- Major 2nd

- Minor 2nd

- Perfect 4th

- Augmented 4th

- Diminished 5th

- Major 7th

- Minor 7th

- All other intervals, but the most common are:

The students were suprised to find that a perfect 4th is considered dissonant in this style. The first thing to understand is that the terms consonant and dissonant are subjective terms that are determined within a style. In this case, a perfect 4th undermines the melodic structure of tonality because it implies a weak inversion. To completely understand this idea requires a deeper knowledge of counterpoint and implied harmony, so at this point, I asked the students to file this away for us to discuss when we get to tonal usage of second inversion chords.

Contrapuntal motion

At its most basic, classifying contrapuntal motion is fairly simple to understand. When we compare two melodic lines, there are five types of possible motion:

- parallel - two lines that move in the same direction and have the same interval size

- similar - both lines move in the same direction but have different interval sizes

- contrary - two lines that move in opposite directions

- oblique - one line stays the same and the other line moves in any direction

- static: neither line moves

- static motion supercedes parallel motion

Each of these types of motion compares the direction of each line (i.e. ascending and descending) and the size of the interval.

Further reading

From Open Music Theory

Types of contrapuntal motion

There are four types of contrapuntal motion between two musical lines. Differentiating these four types of motion is essential to generating good voice-leading, both strict and free.

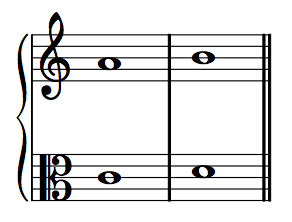

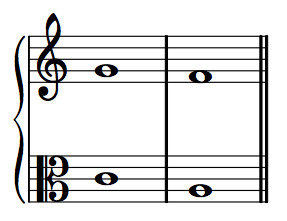

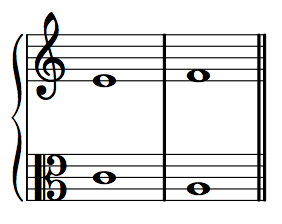

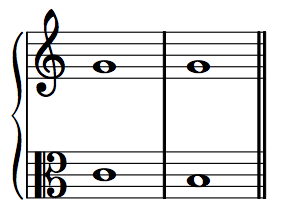

In parallel motion, two voices move in the same direction by the same generic interval. For example, the following two voices both move up by a step. Note also that both dyads form the same generic interval (sixth). This will always be true when two voices move in parallel motion.

In similar motion, also called direct motion, two voices move in the same direction, but by different intervals. For example, the following two voices both move down, but the upper voice moves by step while the lower voice moves by leap. Note also that the two dyads are different generic intervals. This will always be the case with similar or direct motion.

In contrary motion, two voices move in opposite directions—one up, the other down.

In oblique motion, one voice is stationary, while the other voice moves (in either direction). The stationary tone may or may not be rearticulated.

or