Inquiry-Based Music Theory OER Text Book

Lesson 2c - Key Signatures

Class Discussion

Because class time was running short and the students were already familiar with key signatures, we did not spend much time figuring out the basics of key signatures. Instead, we used the examples on the previous page to try to understand “how” key signatures effect keys.

The division of the octave into twelve parts is our brains’ interpretations of a simple mathematical phenomenon. When the frequency of a soundwave doubles, our brains hear those two frequencies as sharing some fundamental commonality, so it interprets those two pitches as the “same” but separated by an octave. Therefore, octaves always have a 2:1 ratio. (A110, A220, A440, and A880 are all A separated by octaves.) The next two simplest ratios ares a 3:2 ratio and a 4:3 ratio, which create a perfect 5th and a perfect 4th respectively.

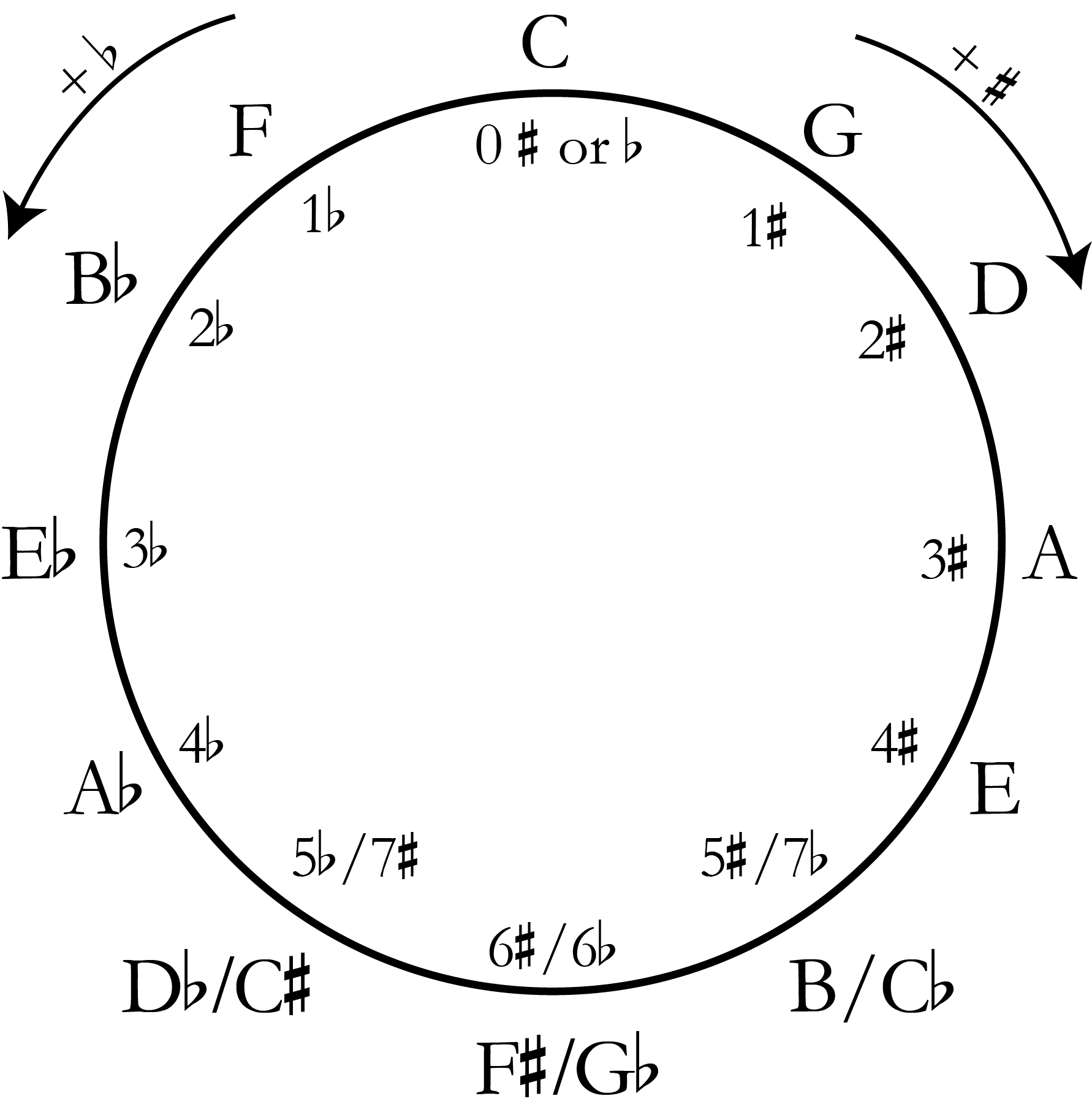

The importance of these ratios is most easily observed in the circle of fifths. If you begin on any pitch-class and begin moving by ascending perfect 5ths (or 4ths), you will find yourself back at the beginning after cycling through all twelve pitch-classes. We call this the circle of fifths.

C - G - D - A - E - B - F-sharp - C-sharp - G-sharp - D-sharp/E-flat - B-flat - F - C

Perhaps more important for our discussion, though, is what happens when we introduce a non-perfect 5th into the pattern. If we begin on a pitch-class and begin moving through ascending perfect 5ths, each new perfect 5th will move us to a new letter. After seven letters, we will begin repeating letters but adding accidentals to them as seen in the circle of fifths above. If, however, we alter the last perfect 5th by a half-step to create a diminished 5th, we can break the pattern and shortcut to the end.

C - G - D - A - E - B - F - C

This slight change creates the necessary tension for keys to function diatonically, so diatonic function could be described as a slight imperfection on an otherwise perfect series of intervals.

This can be further shown by looking at the naturally occuring intervals if we write diatonic 5ths above the notes of a major scale.

When we begin exploring harmonic function in Unit 6, the tension provided by the one non-perfect 5th and its subsequent release will become obvious.

Key signatures reflect the importance of the one non-perfect interval. When studying the consecutive key signatures on the previous page, I asked the students to focus on which scale degree is changed between consecutive keys. The class came up with two rules:

- When a sharp is added to a key, it always raises the 7th scale degree in the new key, thereby creating the new

ti. - When a flat is added to a key, it always lowers the 4th scale degree in the new key, thereby creating the new

fa.

Order of sharps and flats

This directly reflects how diatonic function works; if we change where the one non-perfect 5th occurs, we change the key. We did not need to spend time determining the order of sharps and flats, because the class was already familiar with this from previous courses. It did not surprise them that circle-of-fifths plays a critical role in defining diatonic function and key signatures. The two orders are simply the reverses of each other.

- Order of sharps: F - C - G - D - A - E - B

- Order of flats: B - E - A - D - G - C - F

Further reading

From Open Music Theory

When you’re writing in a single key for an extended period of time, it gets tedious to write out the accidentals over and over again.

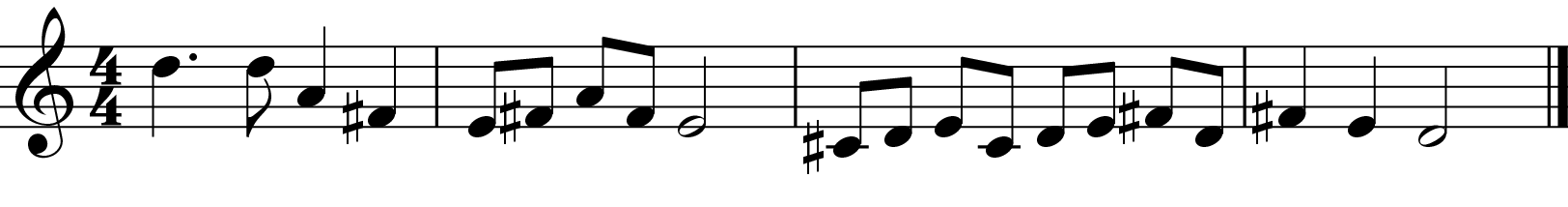

Here is a simple melody in D major, without a key signature.

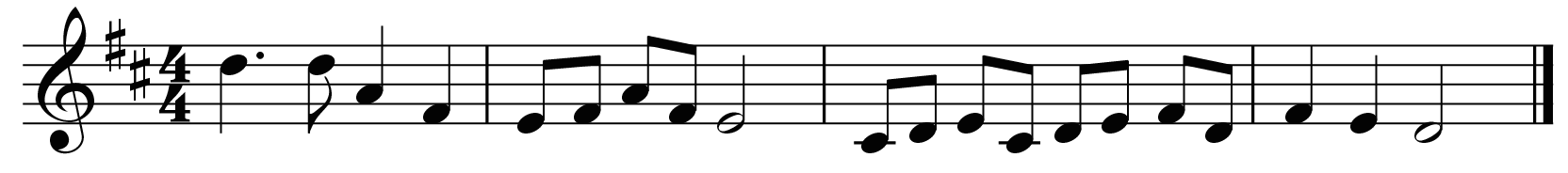

To avoid this, composers used key signatures at the beginning of each staff to remind performers of which pitch classes should have flats or sharps.

Here is the same melody, with the key signature at the beginning of the staff to remind the performer that F and C should be sharp.

The circle of fifths

The circle of fifths is an illustration that has been used in music theory pedagogy for hundreds of years. It conveniently summarizes the key signature needed for any key with up to seven flats or sharps.

But which notes are flat or sharp in a key? To properly use the circle of fifths to figure out a key signature, you’ll need to also remember this mnemonic device, which tells you the order of flats and sharps:

Father Charles Goes Down And Ends Battle.

For sharp keys (clockwise on the circle of fifths), read the mnemonic device forward. For example, the circle of fifths tells us that there are 3 sharps in the key of A major. Which three notes are sharp? The first three notes in the mnemonic device: F(ather), C(harles), and G(oes).

For flat keys (counter-clockwise on the circle of fifths), read the mnemonic device backwards. For example, the circle of fifths tells us that the key of A-flat major has four flats. Which flats? Reading backwards: B(attle), E(nds), A(nd), D(own).

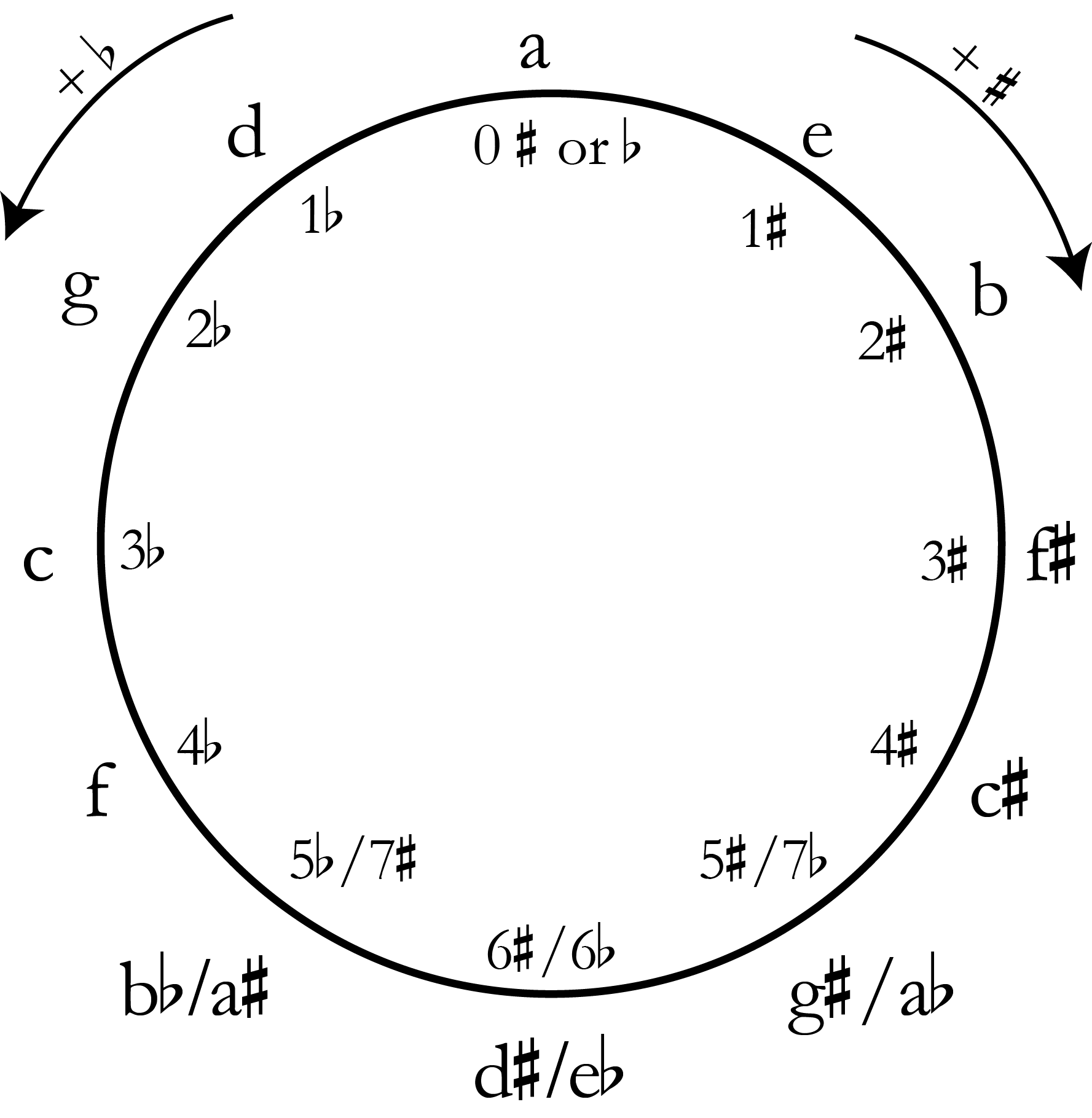

Minor key signatures

Of course, minor keys can use key signatures, too. In fact, for each major key signature, there is a corresponding minor key that shares its signature. Major and minor keys that share the same key signature are called relative keys. For example, both C major and A minor have zero sharps or flats. A minor is considered the relative minor of C major; likewise, C major is considered the relative major of A minor. Compare the minor key circle of fifths below with the major key circle of fifths above, and you’ll see the remaining relative key pairs.

Writing key signatures

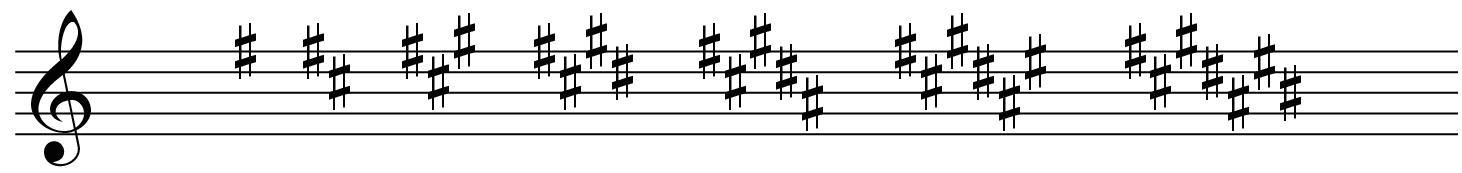

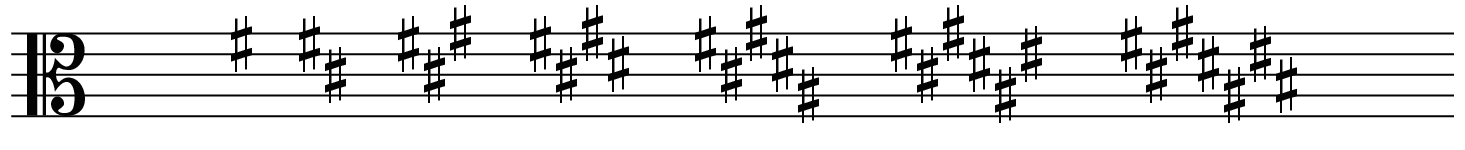

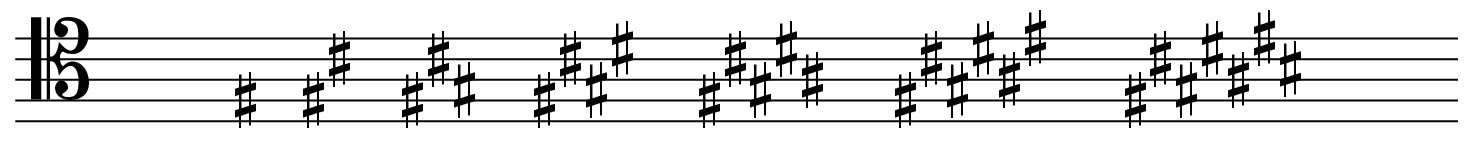

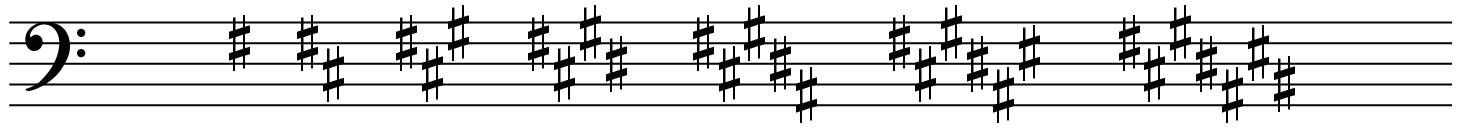

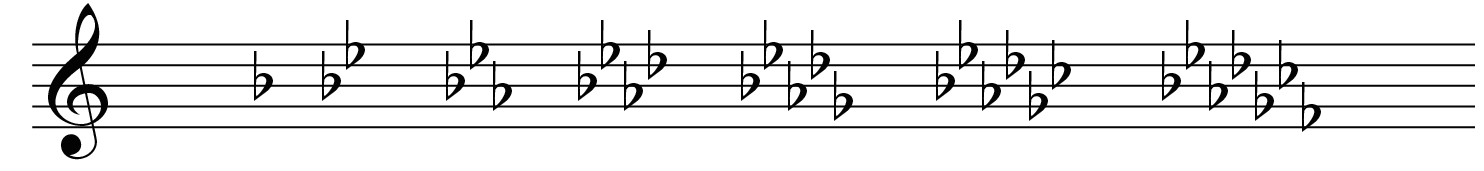

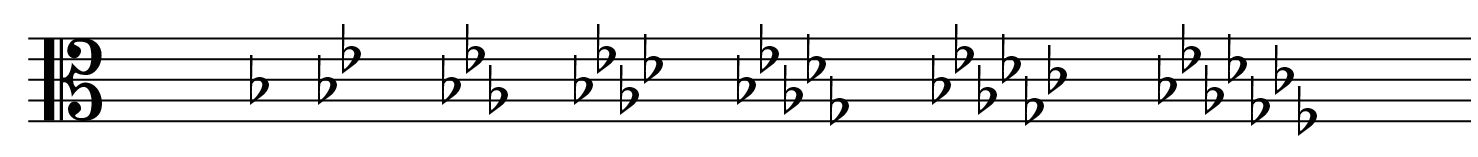

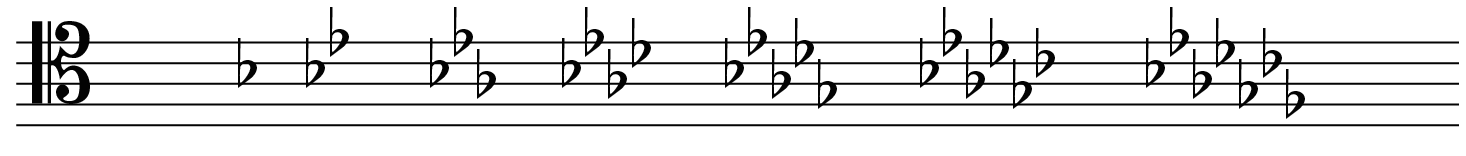

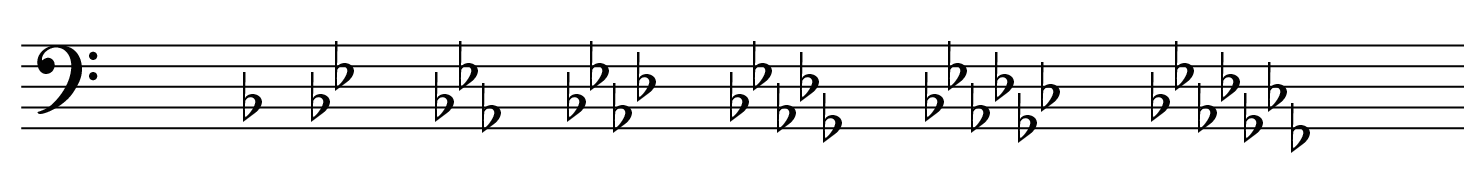

Below is a reference that shows how all of the key signatures should be written on treble, alto, tenor, and bass clefs.